Yachting Monthly

- Digital edition

The true carbon cost of sailing – and why going electric could be less green than you think

- Theo Stocker

- February 7, 2024

New research reaches some surprising conclusions about which propulsion systems might actually have the lowest carbon footprint. Theo Stocker digs into the numbers

A white sail on a blue sea. What could be cleaner than that?’ Sailing nerds might recognise this quote from the all-time greatest sailing film, Wind . Or maybe that’s just me. Anyway, it’s easy to assume that drifting around with the breeze has little impact on the environment, let alone the global climate. But that assumption may be further from the truth than you think.

Certainly, the marine industry is tiny compared to other emitters of greenhouse gases, but it still registers on the scale. Recreational boats account for less than 0.1% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, specifically 0.7% of transportation carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions in the United States and 0.4% of transportation CO₂ emissions in Europe.

Those numbers sound small, but then consider that there are estimated to be 50 million recreational craft globally, with as many as one million new boats being added to that number every year. New research has now been published by the International Council of Marine Industry Associations (ICOMIA) as they seek to plot a way forwards for the leisure marine industry.

The rather bleak headline is that if you want to move away from fossil fuel propulsion, you could easily generate a larger rather than smaller carbon footprint, whether you’re looking at biofuels, hydrogen, electric or hybrid propulsion systems.

The good news, however, is that the devil is in the detail. Make a few compromises to things like range and performance, conduct an honest appraisal of how you actually use your boat, and utilise new and emerging technologies, and you can reduce your boat’s carbon footprint, whether you’re buying a new boat or not.

John Kerry, with his granddaughter, signing the 2016 Paris Agreement on behalf of the US. Photo: Xinhua / Alamy Stock Photo

Paris climate agreement

The Paris Climate Agreement, a legally binding international treaty that seeks to limit global temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, requires signatories to reduce global carbon emissions by 43% by 2030.

While the marine leisure industry might be a tiny proportion of global emissions, it is still a contributor. Given recent protests against superyachts and the perception of sailing and boating as an elite, luxury pastime, ICOMIA wanted to be able to work with regulators to reach policy decisions based on data rather than emotions, assumptions or ideologies.

Article continues below…

There was, however, a ‘vacuum of data’ and while regulators, companies and customers were all trying to take positive steps environmentally, there was very little cold, hard evidence guiding them, leaving potential for flawed choices and the potential dismissal of the best options for reducing the marine industry’s carbon footprint. To fill this void, they commissioned the most detailed research project ever undertaken on the subject in the marine industry.

The result of the project is the 550-page report Pathways to Propulsion Decarbonisation for the Recreational Marine Industry. So far, the report and its data has been shared with the European Commission Department of Growth, the US Dept of Energy and Governments in the United Kingdom, Spain and Sweden.

Infrastructure for new technologies to be adopted is an essential part of assessing their carbon footprint. Photo: Scharfsinn / Alamy Stock Photo

ICOMIA set out to create a robust and holistic analysis of the full environmental impact of all currently available propulsion technologies for recreational vessels under 24m (80ft).

It was to consider the full-life ‘cradle-to-grave’ impact of building, using and disposing of leisure craft. The report covers first-of-its-kind primary research study from Ricardo, a leading global engineering consulting firm. The resulting data took two years to compile and was subject to thorough peer reviews in an attempt to make this the most robust data possible.

ICOMIA’s aim was not to make a pronouncement on what technologies are green or not, but to provide benchmark data against which governments, boat builders, technology developers and you, the sailing public, can make informed choices.

The study covered nine types of vessel up to 24m, including inflatable tenders with small outboards, runabout day motor cruisers, fishing boats, pontoon boats (a large sector in the US), personal watercraft, sailing yachts, inland waterways craft, large displacement motorboats and performance motor yachts.

Steve Bruce, UK MD for ePropulsion, is sceptical about ICOMIA’s report. Photo: Scharfsinn / Alamy Stock

The study was broken down into six steps: exploring the decarbonisation options; conducting a Greenhouse Gas Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to ISO 14044 and 14067 standards including the manufacture, use phase and end of life for energy converters and energy carriers; assessing the total cost of ownership of each system, including purchase, operation and maintenance; analysing the implications of life expectancy, maintenance, performance, safety and availability of each system; analysing the infrastructure implications, before ranking the suitability for each craft type and usage case.

The report is still pretty broad brush strokes, and there are plenty of caveats to the findings. How and where boats are used, what technology is installed, and the supply chains in each of those products have an impact, and ICOMIA says that it is keen that the data acts as a baseline for people to innovate around and find ways of cutting emissions in every part of a boat’s lifecycle.

Even so, some are sceptical about the report. Steve Bruce, Managing Director (UK) of electric engine manufacturer ePropulsion said, ‘I have to say I am extremely disappointed.

It would appear to me that the report has been written with a bias against electrification and has failed to consider several relevant factors, such as the ability to re-purpose and ultimately recycle batteries.

‘It also seems to be based on facts that do not appear to be in line with what we are being told by boat users in our daily conversations, so I would like to better understand precisely where the report writers have decided to select their data from and why.

‘The small amount of hours they suggest boats are used for does not correlate with the actual use profiles we are being asked to support.’

From a user point of view, electric propulsion has many benefits over combustion engines. Photo:

What the research doesn’t do

The report’s authors were keen to emphasise that they were not aiming to stymie certain solutions, but rather to identify the real-world use cases in which these systems are the best to choose, and to highlight where more development and investment is required.

They also noted that the research focuses on propulsion systems, while there are a whole host of other areas in which a pleasure vessel could reduce its carbon footprint, from building materials and manufacturing processes to supply chains, shipping, and disposal. Similarly, how a vessel is used will have a big impact.

ICOMIA CEO Joe Lynch explained, ‘This isn’t to tell people what to do but to help them make the best decision for their use case and allow industry to find solutions, by providing a set of data. It is a point in time study for most popular types of vessel currently in use. We hope to expand this out to more use cases and more emerging technologies, such as foiling, in due course, and aim to turn the work into a more usable life cycle analysis tool as a basis for solid decision making to help decarbonise the marine industry.’

The research did not interrogate the use of recycled goods, for example repurposed pre-used car batteries, or the re-engining of existing yachts, and nor did it pit one type of vessel against another.

It also didn’t give weight to local considerations, such as the need to reduce pollution or noise in ecologically sensitive environments, or increased user enjoyment or a reduction of maintenance.

‘This is a decarbonisation report rather than a usability report,’ said Lynch. ‘There are many other reasons to choose electric-based criteria such as noise, smell, cost, maintenance and so on,’ acknowledging the focus is very much on the global carbon emissions of a vessel’s lifecycle.

Electric cars have a very different set of parameters, meaning they are more able to offset the additional carbon emitted in their manufacture. Photo: Kenny Williamson / Alamy Stock Photo

Cars vs Boats

One of the big assumptions the report seeks to interrogate is that because electric cars, or ‘battery electric vehicles’ (BEV), are thought to be the most environmentally friendly solution for land-based transport, the same will apply on the water. The problem is that there are vast differences between cars and boats, according to the data.

For a start, propelling a boat over a set distance takes roughly 10 times more energy than it takes to move a car. Then you’ve got the fact that most cars are used much more regularly and for longer periods than cruising boats.

This means that of a car’s total lifetime carbon footprint, less than 20% of it is in its manufacture, with almost 80% in its usage – energy supply, exhaust emissions and maintenance – and a bit in its end-of-life disposal. For a boat, the research shows that while some yachts are heavily used, many lie idle for great chunks of time, and they arrived at an average annual usage of a sailing boat’s engine of just 24 hours a year, based on data from engine manufacturer service records and data from the US Environmental Protection Agency.

For the various kinds of motorboats, this increases to between 35 to 48 hours a year. Only a commercially operated rental jet ski had an average use case of over 100 hours a year.

Proportionately, as much as 50% of a boat’s lifetime emissions come from its manufacture, 10% from scrappage and 40% from its usage (and even less when it comes to sailing boats). This gives you a much shorter lever with which to balance out carbon already emitted with a reduction of carbon in usage.

Small dinghies are now frequently powered by electric motors. Photo: Benjamin Sellier

Supply chain carbon

The research analysed the carbon contribution, or global warming potential (GWP), of each stage in the supply chain and lifecycle of each propulsion system, for each of the vessels being considered.

It assumed a like-for-like comparison of energy storage and range, rather than the ‘optimised’ systems referred to later. While these vessels would not be usable in the real world, it made it possible to compare the carbon footprint of equivalent processes within the supply chain.

In the figures given, an inflatable dinghy using an electric outboard can eliminate around 40% of its total GWP from its usage emissions (energy, tank to wake) alone, compared to the petrol-driven baseline. However, this has to offset an almost three-fold increase in its raw materials (propulsion) carbon footprint and a manufacturing footprint that is around two-and-a-half times higher.

Using sustainable marine fuel caused a far bigger increase in the craft’s total footprint, in which the energy well-to-tank actually doubled the craft’s footprint.

For sailing yachts, there is a proportion of the vessels’ total GWP that is attributed to the hull and structure’s raw materials that is several times higher than that of any of the propulsion systems’ raw materials, including electric, though manufacturing impacts are significant.

Mineral extraction and the processes involved are a large part of batteries’ carbon footprint

By far the worst option for a sailing boat was hydrogen, where the well-to-tank impact of the fuel accounted for 40% of the vessel’s total GWP, giving a hydrogen-propelled vessel a carbon footprint twice the size of a fossil fuel-propelled boat.

Both electric and hybrid systems’ GWP were 50% higher than the baseline, with much of this coming from raw materials, manufacture, and surprisingly, maintenance, given electric systems’ almost maintenance-free usage, due to the necessary replacement of the batteries (estimated life span of 12.5 to 15 years).

Even sustainable marine fuel had a higher total impact by about 12% before use-case optimisation, due to a higher energy well-to-tank impact.

Darren Vaux, President of ICOMIA, says, ‘There is a lot of carbon in the supply chain of the batteries, and because there is such low utilisation of hours, it’s very hard to offset. Sailing craft life is long, so the batteries have to be replaced during the course of its life because they don’t have the same longevity.

‘The fascinating thing is that electric motors’ torque profile, lack of noise and all of that are absolutely ideally suited for marine. The challenge is the energy storage, both in terms of the energy density, and also the life of the batteries and the carbon embodied in them from most battery manufacturers.

‘Where manufacturers who operate in a country where they have a high green-energy mix, and a supply chain for manufacture in a factory with a very low carbon footprint, then there’s a competitive advantage to say, “I’ve got a battery that has a very low carbon footprint,” and that will address some of the carbon issue. The energy density of batteries is still significantly lower, but this may be satisfactory in some cases.’

Fitting any kind of alternative propulsion to runabout day boats like this RIB requires a significant compromise.

Realistic comparisons

The five power systems weighed up were all systems that use existing technologies currently available commercially. These were: conventional petrol or diesel internal combustion engines (ICE) as a baseline; sustainable fuels used as drop-in alternatives for fossil fuels in ICEs; hybrid fuel (fossil/sustainable) and electric systems; battery electric drives, and hydrogen ICE or fuel cells.

In order to calculate the life cycle assessment of vessels equipped with the various alternative propulsion systems, it was unrealistic to substitute in systems that provided like-for-like power and range.

As Patrick Hemp, ICOMIA technical consultant explained, ‘We get a lot of questions around the bottom-up approach and why H2 ICE and Battery Electric needed to be optimised. The main reason Ricardo had to do this was because the current baseline speed/range is simply not possible with Hydrogen ICE or Battery Electric (too much weight and volume) and hence, a downsizing was required.’

Fitting any kind of alternative propulsion to runabout day boats like this RIB requires a significant compromise

Runabout motorboat

As an example, a small runaround motorboat may have a typical range of 14 hours and 166 miles. To give the same range in a single duty cycle (one tankful or battery charge) with hydrogen propulsion, fuel storage would need to be around 430% larger than the ICE system and would be 350% heavier, giving the boat a displacement 56% greater.

With electric propulsion, the volume of the batteries for this range would be 360% larger and 820% heavier, with a vessel displacement 133% heavier.

In the calculations, the researchers decided to optimise the power system so that it could still fulfill the way most people use the boat, but with a propulsion system as close to the mass, volume and performance of the existing system as possible.

When aiming to achieve a range of 3 hours and 35 miles for the same small motorboat – a reduction of around 80% – a hydrogen system that was 61% larger and 13% heavier with a displacement increase of just 6% was achievable. For electric power for the same range reduction, the system was 23% larger, while being 81% heavier, with a displacement increase of 16%.

A sailing yacht has a huge fuel-free range if sailed, but most cruisers rely on auxiliary propulsion to keep making progress when conditions don’t suit. Photo: Richard Langdon

Sailing vessel

The calculation for a sailing boat used a baseline of a boat running on diesel, though the HVO fuel figures are identical. With a 21kW / 28hp engine and 70L fuel tank, the boat has a range of 24.5 hours and 147 miles, and there is no increase to mass, volume or displacement for either diesel or HVO.

Change to a hybrid electric drive system running a 21kW / 28hp ICE engine, with a 21kW electric drive. The fuel tank can be reduced slightly to 59L for the same range, but the system volume increases by 69% and would be 137% heavier, increasing the boat’s displacement by 6%.

For an electric or hydrogen system, the systems were specified to a range of 4 hours / 24 miles at an equivalent 6 knots, a reduction in range of around 84%.

The electric system, with a 21kW motor needed a battery capacity of 49kW, which resulted in a system that was actually 18% smaller than the baseline, though it was 61% heavier, and resulted in an additional 3% displacement.

Hybrid Marine specialises in diesel-electric parallel hybrid systems built around new Beta and Yanmar engines

The hydrogen-powered boat, with 21kW engine, had high-pressure fuel tanks to hold 3.7kg of hydrogen. This system was 49% larger than a standard engine and tank, and was 12% heavier, adding just 1% to the boat’s displacement.

Alternative propulsion systems were optimised in this way to enable realistic life cycle assessment comparisons to be made. Looking at the data then, sailors are free to make choices about whether they would be more happy to accept compromises to range, performance, the amount of space on board, and displacement, as well as cost.

Unsurprisingly, the report found alternatives are more expensive than the status quo, albeit within an enormous range. Electric systems as specified in the optimised use cases were 40% to 250% more expensive, 85% to 200% more for hydrogen, 25% to 115% more for hybrid, and 5% to 45% more for using sustainable drop-in marine fuel alternatives.

Large numbers of yachts remained unused or very lightly used, leading to just 24 engine hours a year on average

How much do boats get used?

While ‘battery electric on-road automotive vehicles’ (BEV) reduce CO₂ emissions by between 50% and 70% relative to conventional fossil fuel engines over their lifetime, the initial CO₂ created during the production of an electrical vehicle (EV) can be at least 50% more than a conventional ICE vehicle due to raw materials and the energy intensive process of creating the battery.

This means it takes an electric car 100,000 to 150,000km (62,000 to 93,000 miles) to get the break-even point where it is starting to have a positive impact on carbon emissions, which might take 3-5 years of fairly heavy use.

This also takes into consideration the fact that drivers’ range expectations have, on average, been reduced, so that one battery charge on your car will take you about 60% of the distance your old diesel or petrol car would have done. The cost, size and weight of the batteries would be prohibitive for a like-for-like range, and the environmental cost – mostly attributed to the batteries – would also be even higher.

For boats, those with very high use cases, and where small batteries with limited range can be specified, such as ferries and other commercial vessels, some of the new technologies really do add up in a similar way to cars. But the average leisure cruising yacht (though not, for example, a liveaboard cruiser), has just 24 hours of engine use a year, over its 45-year life span, according to the data.

Diesel engines remain the lowest impact propulsion to manufacture and install, but the emissions from the supply and use of them needs to be reduced

If this seems crazily low, marine surveyor Ben Sutcliffe Davies explained, ‘When I go to survey a vessel, I’m often amazed at how few hours have been put on the engines. It’s rare to find a yacht that’s done much over 50 hours in a year.’

Certainly, many boats will be used far more than the assumptions in this report, but there are also many boats that sit sadly idle, used for a handful of days or hours over the summer. The ‘use case’ of any boat is one of the key deciding factors in what propulsion technology will be the greenest option, and it’s worth remember that this report aims to look at the majority average rather than outliers.

In order to get to the ‘break even’ point on an average GRP cruising yacht, where the new propulsion system’s reduced usage emissions have compensated for its increased manufacturing emissions, you will need to do 60 hours of electric motoring a year (compared to 24 hours average), every year for its 45-year life span.

To get to a point where you have cut your emissions by 50% – the benchmark in the automotive industry – you will need to increase your usage by 600% above the average, or 168 hours of motoring a year on your electric engine. The figures are almost identical for a hybrid system.

Liveaboard and long-term cruisers clearly have a much higher use case, giving them longer to offset carbon with alternative technologies. Photo: Crew Eastern Stream

For a hydrogen system, which has a manufacturing footprint slightly lower than that of battery systems, the break even point comes sooner, with a modest 52% usage increase (36.5 hours), but with a slightly higher carbon footprint in use, a 50% reduction in emissions compared to a diesel engine will take a whopping 192 hours of motoring a year.

Surprising findings

Once the use cases and optimised propulsion systems have been taken into account, for many recreational sailing yachts that match the assumed use case, opting for electric propulsion in a new yacht or converting a used boat to hydrogen, hybrid or electric propulsion will be worse for the environment than sticking with a fossil fuel internal combustion engine (ICE).

For most vessels and average use cases, the best way of reducing environmental impact for the time being is to retain conventional ICE engines, but switch to sustainable synthetic or biofuels such as hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) or e-petrol, the report claimed.

Doing this in a sailing yacht will, over the vessel’s 45-year lifespan with an average annual usage of 24 hours, reduce the vessel’s global warming potential by around 35%, compared to using fossil fuels in an ICE engine. The same benefit applies to both new boats and the numerically more significant existing fleet of boats already in use. Switching to electric or hybrid propulsion may in fact increase the vessel’s global warming potential by over 35%.

If you can find somewhere to buy HVO biofuel, this will be simplest way to immediately cut your carbon

Of the nine vessel types analysed, electrification was only the greenest option for a commercially operated personal water craft used for 156 hours per year over a 12.5 year lifespan. The highest impact of going electric was for a displacement motorboat, used for 48 hours a year over 45 years, where the global warming potential went up by over 80%.

If your vessel, its systems, their manufacture, and your usage don’t match the averages used in this report, then the life-cycle assessment might reach different conclusions, particularly if your usage is higher than average, but it’s worth considering the lifespan emissions when making these decisions.

How we choose to build, propel, and dispose of boats could be limited if their climate impact isn’t addressed

Conclusions

The research concluded that renewable diesel fuel, specifically hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) ICEs can provide the largest global warming potential (GWP) reductions compared to existing ICE propulsion, but only if the fuel is produced using waste feedstocks so that it’s not taking resource away from global food production, and gives the marine industry the greatest chance of decarbonising by as much as 90% by 2035 without compromising a vessel’s range or performance.

That’s all very well, and marinas with existing fuel supply infrastructure should be able to adapt easily, but it would require a huge increase in the supply of HVO in order to facilitate that change, and that capacity just isn’t there at the moment. As the report notes, ‘There is considerable uncertainty over the availability of these fuels through to 2035, and caution must be taken to guarantee that e-fuels are produced using low-carbon electricity sources and biofuels are produced with low GWP feedstocks.’

It also concludes that because electric-only systems ‘may have a higher GHG contribution from raw materials and manufacturing than conventional propulsion systems’, vessels that have low-usage cases are unlikely to ‘yield a reduction in greenhouse gases’ over their lifespans. Boats that are in frequent and prolonged use may be more likely to reach the break-even point, while hydrogen and hybrid systems may, in some cases, be the greenest option.

ICOMIA is now working on making a full life-cycle assessment tool available to the industry so that boats and use cases can be examined on a case by case basis. The report is a snapshot of the LCA for each type of boat, and a series of assumptions made about its usage.

ICOMIA President Darren Vaux, explains, ‘These use cases should cover the majority of the market, but there will be outliers that don’t fit these use cases. We are trying to move the dial on meeting the Paris Agreement for decarbonisation of the marine industry. At the moment, the only thing that will get us there is drop-in HVO fuels.

‘We need to focus policy-makers’ minds,’ Vaux continues. ‘We’re building infrastructure for electric vehicles, but we also need an infrastructure for the supply of sustainable fuels. We also want to challenge innovation, to encourage the industry to use the data-set as a challenge, with a clear focus on what the supply chain carbon impacts are.

‘Our data-set is the majority case, but that leaves room for boat builders to find ways around it, to say, “We’re better than that.”’

Enjoyed reading this?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price .

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals .

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

Follow us on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram.

What Is Greener? Boat vs. Plane Emissions

Olivia Young is a writer, fact checker, and green living expert passionate about tiny living, climate advocacy, and all things nature. She holds a degree in Journalism from Ohio University.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/DSC00327-3-e1603657890293-8c51ab129699408f91501471597ee7b3.jpg)

- Ohio University

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ScreenShot2021-04-07at1.57.45PM-bcef177316c94cdf998457c694cce6d5.png)

- University of Tennessee

Stephen Frink / Getty Images

- Public Transportation

In 2019, after boycotting air travel on account of its colossal carbon footprint, Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg set sail on a 15-day transatlantic voyage from the U.K. to New York for a U.N. Climate Action Summit. Her widely publicized endorsement of slow, carbon-neutral travel shone a light on the environmental impact of flying , ultimately leading to a whole flight-free movement. But alas, traveling a la Thunberg (i.e., via sailboat) is perhaps too technical and time-consuming to be considered a viable means of transportation, and trading airplanes for cruise ships can lead to an even bigger problem, considering boats are on par with planes in their greenhouse gas emissions. In some ways, watercraft can be even more polluting.

Several factors should be considered when weighing the emissions rate of boats versus planes, such as the vehicle's age, its fuel type and efficiency, the length of the trip, number of passengers, and so forth. Learn more about the different kinds of gasses passenger planes and cruise ships emit, the environmental impact of those gases, and which of these notoriously dirty modes of transport is greener.

Airplane Emissions

LeoPatrizi / Getty Images

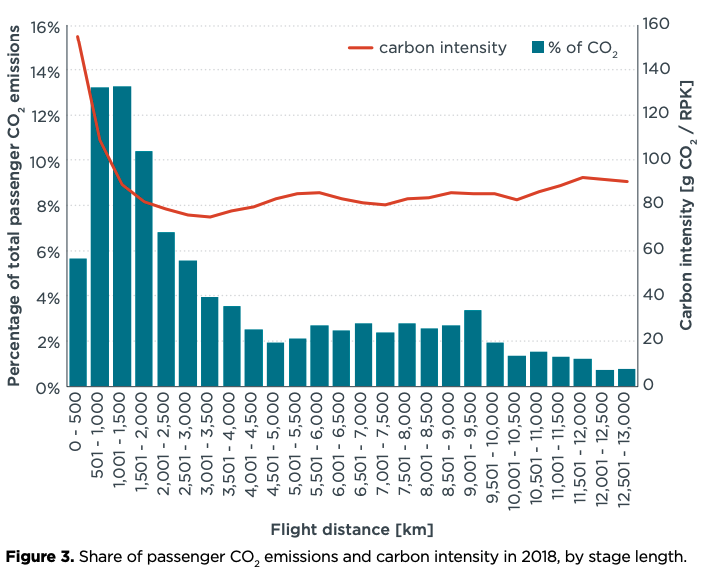

Of the reported 16.2% of global greenhouse gas emissions for which transportation, in general, accounts, air transport (of both people and freight) is responsible for 1.9%. A 2018 report from the International Council on Clean Transportation said passenger transport accounted for 81% of total aviation emissions—that's 747 million metric tons of secreted carbon dioxide per year. The International Council on Clean Transportation says if the aviation industry were a country, it would be the sixth top greenhouse gas emitter. In the U.S. alone, emissions from domestic flights have increased by 17% since 1990, and passenger air travel continues to have a positive growth rate globally, interfering with efforts to slow global warming.

Carbon dioxide makes up about 70% of aircraft emissions. CO2 is the most widely understood greenhouse gas, which is produced by the consumption of jet fuel. The type of plane, number of passengers, and fuel efficiency are all factors in exactly how much CO2 a plane emits, but the Environmental and Energy Study Institute defines the ratio as about three pounds per pound of fuel consumed, "regardless of the phase of flight." A chunk of the gas emitted by a single flight, the nonprofit notes, can linger in the atmosphere for thousands of years.

In addition to CO2, though, burning jet fuel also generates nitrogen oxides , classified as indirect greenhouse gases because they contribute to the creation of ozone. Although still a relatively small component of total aviation emissions, NOx emissions from air travel are increasing at a faster rate than CO2, doubling from 1990 to 2014. That increase can be attributed to a growing aviation industry—one whose primary environmental mission is to curb emissions from the more notorious CO2.

Of course, not all planes are created equal, and while none are truly eco-friendly, some are greener than others. The Airbus A319, for instance, outperforms the classic Boeing 737 of its size (the 300 model) in fuel efficiency. It consumes about 650 gallons of fuel per hour compared with the latter's 800 gallons per hour. The Airbus A380 was briefly marketed as a "Gentle Green Giant," but the ICCT notes that the Boeing 787-9 was 60% more fuel-efficient than the A380 in 2016.

The Effects of Radiative Forcing

The EESI says only 10% of gases produced by planes are emitted during the takeoff and landing (including the ascent and descent); the rest occur at 3,000 feet and higher. This is especially damaging because of radiative forcing, a measure of how much light gets absorbed by Earth and how much is radiated back to space. The contrails—vapor trails—planes leave in their wake cause radiative forcing and trap gases high in the atmosphere, where they cause more damage than at the ground level.

Boat Emissions

Marcutti / Getty Images

Like planes, boats also emit a cocktail of toxic greenhouse gases—including but not limited to CO2 and NOx. The amount emitted, likewise, depends on the ship's size, age, average cruising speed, number of passengers, and length of trip. There are all sorts of watercraft, but when comparing the footprint of maritime transport—accounting for 2.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions—to that of air travel, it's perhaps most logical to analyze the vessel most similar in size to a passenger plane: a cruise ship.

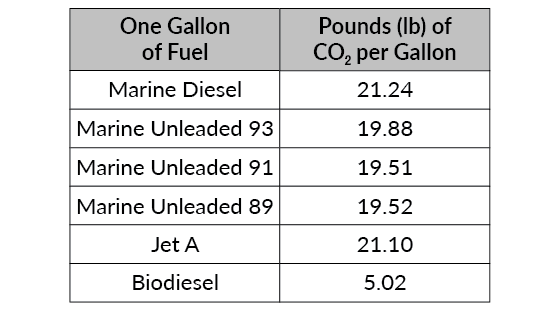

Traditional cruise ships run on diesel, one of the most CO2-producing fuel types available. According to Sailors for the Sea, a nonprofit ocean conservation organization affiliated with Oceana, marine diesel generates 21.24 pounds of CO2 per gallon of fuel. What's more, cruise ships emit black carbon—soot produced by the combustion of fossil fuels and biomass—and almost six times as much as an oil tanker emits, at that. According to a 2015 report from the ICCT, cruise ships account for 6% of marine black carbon emissions despite making up only 1% of ships globally. The warming effect black carbon has on the climate is thought to be up to 1,500 times stronger than that of CO2.

The European Federation for Transport and Environment found in a continent-wide study on luxury cruise ship emissions that the amount of NOx released by these hefty liners was equivalent to 15% of Europe's entire car fleet. It also found that port cities throughout Europe suffered from air pollution caused by extraordinarily high levels of sulfur oxides generated by the ships. In Barcelona, for instance, ships are generating five times more SOx than cars.

Large cruise ships designed for long-haul trips even have their own incinerators. The average cruise ship produces seven tons of solid waste every day, which leads to a reported 15 billion pounds of trash being dumped into oceans (as ash, mostly) per year. Besides the direct impact this has on marine life, the incineration process itself generates additional emissions of CO2, NOx, sulfur dioxide , ammonia, and other toxic compounds.

Ocean Acidification

In the same way planes intensify their emissions by belching greenhouse gases at altitude, emissions from ships are extra harmful because the CO2 that escapes their exhausts is promptly absorbed by seawater. Over time, this can change the pH of the ocean—a phenomenon called ocean acidification . Because increased acidity is caused by a reduction in the amount of carbonate, shells made of calcium carbonate may dissolve, and fish will find it difficult to form new ones. Ocean acidification also takes a toll on coral, whose skeletons are made of a form of calcium carbonate called aragonite.

Which Is Greener?

Daniel Piraino / EyeEm / Getty Images

A 2011 case study of cruise ships in Dubrovnik, Croatia, estimated that the average CO2 emitted per person, per mile on a medium-sized 3,000-passenger cruise ship was 1.4 pounds. By that calculation, a round-trip cruise from Port Canaveral in Orlando, Florida, to Nassau, Bahamas—a popular, 350-mile transatlantic route frequented by Royal Caribbean International, Carnival, and Norwegian Cruise Line—would equal about 980 pounds of carbon emissions per person. That same return route, if traveled from Orlando International Airport to Nassau's Lynden Pindling International Airport in the economy class of a passenger aircraft, would add up to only 368 pounds of CO2 emitted per person, according to the International Civil Aviation Organization's Carbon Emissions Calculator. And that's only emissions from carbon, not NOx or any other gases.

Of course, a case can be made that ferries and other, less-polluting boats provide eco-friendly alternatives to air travel. This could be the case for overwater routes that ferries can handle, such as the heavily trafficked route from Melbourne to Tasmania, Australia, or the shorter-but-equally-busy route between Morocco and Spain. But the slower-moving vessels that boast entire waterparks and golf courses on board are likely to always trump aviation in terms of greenhouse gas emissions.

Tips for Reducing Your Carbon Footprint While Traveling

- Before booking a flight or a cruise, do your research on which airlines and cruise lines are taking steps to reduce their carbon footprints. Friends of the Earth regularly creates " cruise ship report cards " in which all the major cruise operators are given a grade based on air pollution reduction, sewage treatment, water quality compliance, and other factors. Atmosfair has released a similar ranking of airlines based on fuel efficiency.

- Whether traveling by air or water, remember that the shorter the trip, the greener. Choose direct flights over ones with multiple stops to minimize mileage.

- Consider carbon offsetting your travel. Many airlines are now offering this as an additional service, but you can also donate to a carbon offsetting program of your choice, such as Carbonfund.org or Sustainable Travel International .

" Transport Sector CO2 Emissions by Mode in the Sustainable Development Scenario, 2000-2030 ." International Energy Agency .

Ritchie, Hannah. " Sector by Sector: Where Do Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Come From? " Our World in Data , 2020.

Graver, Brandon, et al. " CO2 Emissions From Commercial Aviation, 2018. " The International Council on Clean Transportation , 2019.

" Airplane Emissions ." Center for Biological Diversity .

Overton, Jeff. " Fact Sheet | The Growth in Greenhouse Gas Emissions From Commercial Aviation ." Environmental and Energy Study Institute , 2019.

" European Aviation Environmental Report 2016 ." European Union Aviation Safety Agency, 2016, p. 6.

Rutherford, Dan. " Size Matters for Aircraft Fuel Efficiency. Just Not in the Way That You Think ." The International Council on Clean Transportation , 2018.

Karcher, Bernd. " Formation and Radiative Forcing of Contrail Cirrus ." Nature Communications , vol. 9, no. 1824, 2018., doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04068-0

" Reducing Emissions From the Shipping Sector ." European Commission .

" Carbon Footprint ." Sailors for the Sea .

Comer, Bryan, et al. " Black Carbon Emissions and Fuel Use in Global Shipping ." The International Council for Clean Transportation , 2015, p. vii.

" Black Carbon ." Climate & Clean Air Coalition .

Abbasov, Faig, et al. " One Corporation to Pollute Them All ." The European Federation for Transport and Environment , 2019, pp. 8-11.

" Needless Cruise Pollution: Passengers Want Sewage Dumping Stopped ." Oceana, p. 4.

Caric, Hrvoje. " Cruising Tourism Environmental Impacts: Case Study of Dubrovnik, Croatia ." Journal of Coastal Research, Special Issue no. 61, 2011, pp. 104-113.

" ICAO Carbon Emissions Calculator ." International Civil Aviation Organization .

- What Is Greener? Flying vs. Driving

- Hydrogen-Fueled Planes Could Meet One-Third of Air Travel Demands by 2050

- Do You Have to Modify a Diesel Engine to Run It on Vegetable Oil?

- Plane, Train or Automobile: Which Has the Biggest Footprint?

- Are Electric Cars Truly Better for the Environment?

- Should We Just Stop Flying to Conferences?

- Amsterdam's Canal Boats Are Going Electric Too

- New Report Questions Whether We Should Bring Back Supersonic Transport

- Airbus Proposes Planes Fueled by Liquid Hydrogen

- Train vs Plane: Which Is the Better Way?

- KLM to Fly on 'Sustainable Aviation Fuel' Made From Cooking Oil

- We’re Thinking About Flying All Wrong

- I Am Flying to Another Conference and I Know I Shouldn't

- Flying Private Is Taking Off Due to Pandemic and Airport Pandemonium

- Air Canada Flew Plane Using 50% Cooking Oil Biofuel for First Time

- Hybrid vs Electric Cars: Which Is Greener?

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Climate Crisis Gives Sailing Ships a Second Wind

In February, 1912, Londoners packed a dock on the River Thames to gawk at the Selandia, a ship that could race through the water without any sails or smokestacks. Winston Churchill, then the minister in charge of the British Royal Navy, declared it “the most perfect maritime masterpiece of the twentieth century.” But, as the Selandia continued its journey around the world, some onlookers were so spooked that they called it the Devil Ship.

The Selandia, a Danish vessel that measured three hundred and seventy feet, was one of the first oceangoing ships to run on diesel power. So-called devil ships inaugurated a new age of petroleum on the high seas; by the twenty-first century, nearly ninety per cent of the world’s products spent time on diesel-powered vessels. The shipping industry created a mind-bending supply chain in which an apple from halfway around the world often costs less than one from a nearby orchard.

Diesel ships never entirely stamped out the sailing ships that once reigned supreme, however. In 1920, a Dutch shipbuilder fashioned a sailing schooner named the Avontuur and put it to work carrying cargo, which it did for the rest of the century. By 2012, the Avontuur was ferrying passengers on the Dutch coast; at more than ninety years old, it probably seemed destined for a maritime museum or a scrap heap. But that year a United Nations climate report warned that the planet was careening toward an era of extreme weather and disasters, in which escalating heat waves, fires, and storms could become the norm. Humans had the power to avert these crises—but only if they took rapid action to end their dependence on fossil fuels.

Two years later, Cornelius Bockermann, a German sea captain who had worked with oil companies, bought the Avontuur and made it the flagship of a company called Timbercoast. His mission was to eliminate pollution caused by cargo shipping. Bockermann had witnessed the harms of diesel ships; on the high seas, beyond the reach of most environmental regulations, the descendants of the Selandia burn millions of gallons of thick sludge left over from the oil-refining process. The shipping industry, he knew, was one of the dirtiest on the planet, spewing roughly three per cent of the world’s climate pollution—as much as the aviation industry. After having the Avontuur restored, he captained the ship, hired a small crew, recruited some volunteer shipmates, and put the vessel back to work. It could carry only about a hundred tons of cargo—a tiny amount compared with the more than twenty thousand tons that a container ship can carry—but customers hired Timbercoast to deliver coffee, cocoa, rum, and olive oil.

Bockermann’s company is one of several founded on a provocative idea: What if shipping’s history could inspire its future? For centuries, the cargo industry ran on clean wind power—and it could again. As the climate crisis has escalated, and the pandemic has exposed weaknesses in global supply chains, the movement to decarbonize shipping has spread. What was once the dream of a few enterprising idealists has become a business opportunity that startups and sprawling multinationals alike are chasing.

Christiaan De Beukelaer, an anthropologist who was researching the nascent field of eco-friendly shipping, came aboard the Avontuur as a shipmate in February, 2020. He was about three weeks into his voyage when, on March 17th, the ship’s temperamental dot-matrix printer spewed out an emergency message that Bockermann had sent from shore. “The world as you know it no longer exists,” the dispatch said. Coronavirus lockdowns had shut borders and ports in dozens of countries. De Beukelaer and the rest of the crew were now marooned indefinitely aboard the Avontuur.

In the Gulf of Mexico, they rediscovered the difficult realities of wind-powered transport. “We were going around in circles, taking the sails down and up again because of the squalls,” De Beukelaer told me. The ship zigzagged for weeks, and supplies dwindled. After the fruits and vegetables were gone, the crew ate short rations. The cook worried that they’d run out of gas for the stove. But elsewhere, the pandemic was revealing just how vulnerable the entire shipping industry might be.

In 2020, with so many ports clogged and ships stuck at sea, store shelves emptied, and customers waited months for items such as cars and refrigerators. The following year, the Ever Given, a container ship about the size of the Empire State Building, ran aground in the middle of the Suez Canal. It delayed shipping traffic between Europe and Asia for months, a seeming metaphor for a world held hostage by diesel-guzzling behemoths. Oil prices rose while tankers, carrying almost ten per cent of the world’s daily oil consumption, waited their turn. A meme christened the ship the Least Fucks Ever Given.

Shipping’s sudden visibility reinvigorated activist organizations, which have long pressured cargo owners to clean up their operations, De Beukelaer told me. Members from the environmentalist group Extinction Rebellion spun off a political-art collective called Ocean Rebellion; its inaugural demonstration projected messages like “TAX SHIPPING FUEL NOW” onto the side of a cruise ship. In 2021, a consortium of climate and public-health groups launched the Ship It Zero campaign, calling on big retailers, including Target and Walmart, to transport their products with cargo carriers that are “taking immediate steps to end emissions,” and to “sign contracts now to ship your goods on the world’s first zero-emissions ships.”

In January, De Beukelaer published “ Trade Winds ,” a book about his five months at sea during the pandemic. His story doubles as a plea to clean up the shipping industry. It takes “fifty thousand Londons worth of air pollution,” he writes, to ship eleven billion tons of cargo each year—about one and a half tons for each person on the planet. In his view, consumers and corporations must take responsibility for the environmental mayhem that they cause. And they can start to do that, he writes, if sailing ships make an epic comeback.

For wind power to push the shipping industry forward, it will need to reach the biggest players in the business. In 2018, Cargill, the largest privately held American company, pledged to cut its direct greenhouse-gas emissions by ten per cent within seven years. Five months later, the company’s maritime division, which manages a fleet of about six hundred ships, announced a CO 2 Challenge. Inventors around the world were invited to propose novel ways to reduce carbon emissions of cargo vessels.

Cargill transports more than two hundred million tons of cargo, including soybeans, fertilizers, and iron ore, each year. It’s not easy to decarbonize such a sprawling business; in 2017, Cargill’s global operations emitted as much as several million cars. That same year, an environmental group, Mighty Earth, reported that the company was fuelling deforestation in South America, by buying soybeans in places where megafarms were swallowing woodlands. Because forests store carbon, deforestation has a major carbon footprint. (Cargill once pledged to eliminate deforestation from its supply chains by 2020, but says it is now working toward a target of 2030.)

The CO 2 Challenge identified other areas in which Cargill could reduce its climate pollution. “We opened it up to everyone out there,” Jan Dieleman, the head of the division, told me. “We got something like a hundred and eighty ideas, including some crazy ones.” One proposal suggested freezing CO 2 emissions into dry ice. Another recommended nuclear-powered ships. A third went so big on batteries that it left little room for cargo. Some of the winning entries sounded as daffy as the rejects. One of them, from a startup called BAR Technologies, imagined airplane-style wings rising nearly a hundred and fifty feet from the deck of a cargo ship.

The idea of powering ships with rigid wings dates back at least to the nineteen-sixties, when an English aeronautics engineer named John Walker spent his weekends in a cranky, old yacht. One day, he was hopping around the cockpit, trying to coax the mainsail to swing into position, and he failed to notice that a rope had wrapped around his ankles. When the sail caught the wind, the rope pulled him into the air. After that humiliating incident, he began to wonder why sailboats had evolved so little in hundreds of years. Wasn’t there some way to improve on this messy system of ropes and booms?

In 1969, news footage showed Walker—a trim and bearded Old Spice sort of man—at the helm of what he called the Plane-Sail Trimaran. Piloting the boat, he once said, felt like flying a plane. Where the mainsail should have been, four rigid sails stuck straight up into the air, like window blinds turned vertically; each one had the shape of an airfoil and generated forward thrust. They also allowed him to carve the wind with more control than a cloth sail would allow: instead of turning the entire boat at an angle to catch the wind, by either tacking or jibing, Walker could simply spin a crank, and the wings above his head would swivel into a configuration that would drive the boat forward, sideways, or even in reverse. He became obsessed with his creation. “My wife complained that I’m not the man she married and she is right,” he told a reporter, in 1970.

During the energy crisis of the nineteen-seventies, Walker wondered whether his winged yacht could also help to solve environmental problems. He founded a company called Walker Wingsails, built demonstration vessels, and, in 1989, advertised a “wingsail cruising yacht” with “fingertip control by a single person.” His vision of no-emissions shipping now seems far ahead of its time. “Using only the free clean ocean winds, the Walker wingsail technology can make a valuable contribution to the control of pollution and the greenhouse effect,” the ad declared. In 1991, the New York Times deemed his winged innovation “the most radical sailboat to ever slip into the harbor.” But not all the reviews were positive. A few years later, when a sailing magazine questioned the performance of his wings, Walker sued for libel and became tangled up in a high-profile case. Though he eventually won, his company went bust.

Around the turn of the twenty-first century, boat designers experimented with winglike sails for a different reason: they wanted to break speed records on racing yachts. Competitors in the America’s Cup, the most prestigious U.S. yacht prize, showed that a combination of rigid wing sails and hydrofoils, which work like underwater airplane wings, propels the yachts along the surface of the water. The winged catamarans, which looked like seabirds skimming for fish, proved to be so blazingly fast that in 2010 the Cup put them into a class of their own. After the Cup banned competitors from testing out their models in water tanks or wind tunnels, many of the teams embraced computer modelling and created elaborate simulations of yachts gliding across virtual oceans.

In advance of the 2017 America’s Cup, a British team hired a group of engineers and created one of the world’s most powerful wing sails. Their entry lost the race, but the designers weren’t ready to part ways and instead spun off BAR Technologies. The team decided, “We’re not going to lose all these great people, and we’re not going to lose all these simulation tools,” John Cooper, the company’s C.E.O., told me. A year later, it won a contract with Cargill to fit its proprietary wing sails, WindWings, onto a bulk carrier.

A diesel ship retrofitted with wing sails could reduce its fuel consumption by as much as thirty per cent, according to a BAR Technologies simulation. When I ran that figure by Elizabeth Lindstad, a chief scientist at SINTEF Ocean, an independent think tank that advises maritime companies, she described it as optimistic but possible, at least along trade routes with the right wind conditions. Paul Sclavounos, a professor of naval architecture and mechanical engineering at M.I.T., agreed. Savings on that scale, he said, could reshape the economics of shipping. Many multinational companies, including Cargill, lease their vessels from shipbuilders and pay for fuel expenses. It can cost more than twenty-four thousand dollars per day to fuel a bulk carrier; a company that adds wing sails to one ship could save thousands per day, and “pay back its investment in a year or two,” Sclavounos told me. The wings could then provide decades of propulsion for only the price of maintenance. “It’s clearly a relatively inexpensive technology,” he said. “It makes a lot of sense.”

Wind propulsion will help some ships more than others. Container ships are responsible for about twenty-three per cent of shipping emissions, according to a report from the International Council on Clean Transportation, but it’s difficult to squeeze sails onto a deck that’s cluttered with metal boxes. In contrast, bulk carriers, which are responsible for roughly nineteen per cent of shipping emissions, are perfect laboratories for wind propulsion, thanks to their open decks and relatively small size. The same goes for more specialized vessels that carry vehicles such as cars, trucks, and trains. These Ro-Ro ships—short for “roll on, roll off”—don’t need any help from cranes when they sail into port, and they tend to stash their cargo in a hold, leaving plenty of room on deck for sails.

Of course, you can’t just slap an airplane wing onto the deck of a ship and expect it to work. Airplane wings provide lift, but rely on jet engines to provide thrust; a wing sail, in contrast, must provide thrust of its own. Engineers are now studying how many wings they can cram onto the deck of a ship, and how high they can go without threatening the stability of the vessel. Some are building wing sails that fold or telescope so that they don’t bump into bridges or cranes. Cargill plans to try out its first set of WindWings on a commercial route in early July; BAR Technologies is also installing WindWings on a ship owned by Berge Bulk this year. Cooper told me, “If you fast-forward three or four years, we’re looking at building hundreds of wings.”

A diesel ship that’s retrofitted with wing sails will pollute much less than its peers—but it still won’t be clean. “We know that wind alone is not going to bring us to zero carbon,” Dieleman told me. In the future, ships will likely need to swap out dirty fuels for alternatives with low carbon footprints. Cargill has four vessels in production that run on methanol, which produces far lower emissions at sea. At the moment, though, most of the methanol on the market is “brown,” Dieleman said—in other words, made from fossil fuels. Bio-methanol can be made from agricultural waste or seaweed, and another fuel, green hydrogen, can be generated from water and clean electricity. But they are still a kind of Unobtanium, because no one has yet figured out how to produce trillions of gallons at low cost.

Then again, why not rethink cargo ships entirely—from the keel up—so as to squeeze as much power as possible from the wind? Lindstad, the scientist at SINTEF Ocean, and her research partners have argued that the ships of the future should combine wind propulsion with slender hulls that reduce drag. They estimate that some vessels designed in this way could cut down fuel use by as much as fifty per cent. Cargo ships may also need to chart new courses, following trade winds that were largely ignored in the age of diesel.

A few months ago, I travelled to Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, a Canadian port town known for its fisheries and shipyards, to meet Danielle Southcott, a sustainable-shipping entrepreneur who’d recently moved there. On the day we met, in a loft that serves as an event space, she was introducing her company, Veer Group, to about fifty people, mostly from the local shipping community. The crowd was a blur of leather jackets, scruffy beards, interesting glasses, and knit caps: artsy, but also appropriately attired to carve a mizzenmast or hack some barnacles off a hull. Southcott, at thirty-three, fit right in—she wore all black, and her long, dark hair curtained her face each time she glanced down at her notes.

When she flashed a rendering of a sailing ship onto the screen, I could sense the collective puzzlement in the room. It looked like the ghost of a traditional three-masted clipper, with no visible cables or ropes.

A man raised his hand. “I don’t see any rigging,” he said.

Southcott explained that Veer was using a sailing system called the DynaRig, which had been tested on two luxury yachts, the Maltese Falcon and the Black Pearl. Though the sails are made from cloth rather than rigid panels, they have something in common with wing sails: they’re shaped much like broad airplane wings and are controlled through a computer. Each mast can rotate more than a hundred and eighty degrees.

The ideal cargo for Veer’s first ship, Southcott said, would be something like designer shoes: they have high markups and low weights, and customers pay a premium for the latest and greatest. Imagine the fashionistas, she went on, who would pay upmarket prices for net-zero delivery. According to design plans, the ship could attain speeds of eighteen knots, or more than twenty miles per hour, on wind alone. As she explained her stiletto-heeled business model to her steel-toe-boot audience, the mood seemed to shift from skepticism to glee. She was questioning a basic assumption in the shipping industry—the cheaper, the better—and imagining a new one: the better, the better.

Later that evening, some audience members decamped to a creaky wooden pub called the Knot, and I eavesdropped as two master mariners vented about the shoddiness of container ships. The ships would be more fuel efficient with rounded hulls, they observed, but they’re built like steel boxes to save money. The think tank at the bar agreed that a Veer-style ship would work just fine from a technical standpoint—one guy even assured Southcott that gantry cranes, which pluck boxes off of ships, would be able to maneuver around masts without knocking them over. But they wondered whether she could build a business in an industry that usually competes on rock-bottom prices.

In Southcott’s telling, the key variable for upscale retailers is not cost but speed. She’d learned that lesson in 2021, she told me, when she was running a company that built wooden sailing ships for freight delivery. Her potential clients were eager to lease a net-zero cargo vessel—but not if it plodded along so slowly that it added days or weeks to the delivery date. So she contacted a friend at Dykstra Naval Architects, a Dutch firm that designs classic and modern yachts. Southcott brought preliminary renderings of a Veer ship, to be built from composite materials and steel, to the COP 26 climate conference, in Glasgow. Soon after she announced her venture, she raised six hundred thousand dollars from four investors. She used the money to hire Dykstra engineers to draw up technical plans for the first ship, and to assemble a startup team.

Southcott told me that her investors have now pledged more than two million dollars, enough for her to seek financing from a bank and submit bids to shipyards that could build Veer’s first ship. She hopes to build it in a country where she can use “ green steel ,” which is manufactured without fossil fuels. If she succeeds, she’ll be working in a new slice of the shipping sector—one that’s far smaller than the world of container ships and bulk carriers, but one with a clearer path toward zero emissions. The C.E.O. of Dykstra, Thys Nikkels, told me that, with souped-up sails and turbines that can charge batteries, it’s already possible to build a speedy ship with a small footprint. “On a sailing yacht, that’s quite feasible,” he said. “But it hasn’t been done on a commercially operated cargo vessel.”

There’s at least one other direction in which cargo ships could innovate: up. “The higher you go, the higher the wind velocity,” Mikael Razola, the technical director at Oceanbird, a Swedish company affiliated with the shipping company Wallenius Marine, told me. Oceanbird researchers have used lidar imaging to map wind pressure from the surface of the ocean to an altitude of nearly seven hundred feet. The company has designed wings for a Ro-Ro ship, set to launch next year, that will be outfitted with six towering wing sails that reach more than one hundred and thirty feet into the air. The wings will be paired with a special lightweight hull that is aerodynamic and reduces drag. The company claims that the design will reduce the ship’s emissions by a striking sixty per cent. But the trade-off for that efficiency is speed: on existing routes, the car carrier with sails will take days longer than other ships.

In February, I opened my laptop and beamed into a factory outside of Shanghai, where workers were hurrying to build WindWings for Cargill’s fleet. A representative of Yara Marine Technologies, which is leading the installation, had agreed to a virtual tour of the factory on the condition that I refrain from quoting the “cameraman”—a factory worker who walked me around the facility with his phone. As it turned out, the language barrier was big enough that my guide communicated mostly through gestures. He started his tour by pointing his phone at a simplified diagram of the wings, which looked like the instructions for some IKEA furniture. A mast—basically, a metal tube with arms—would be fitted with panels to catch the wind; this assembly would sit on a swivelling base that could turn the wings around. The IKEA vibes ended there. When my guide pointed his phone up, I saw the huge steel frame of a WindWing waiting to be filled with hydraulic piping and wiring for sensors, which will detect air pressure.

The guide walked me to a welding platform, where workers scurried around a mast that had been tipped onto its side. Laid horizontally, the steel frame turned into a kind of enormous hallway, with eight or ten feet of headroom for the welders who worked inside it. As I watched a man in white coveralls climb into the base of one of the masts, its scale sank in. The man looked like an action figure. The tour continued to a nearby dock, where the masts would be fitted onto ships. The wings would be so immense that they would block the sight lines across the deck, so, rather than navigating with the naked eye, the crew would depend on digital cameras.

One chapter in “Trade Winds,” De Beukelaer’s book about his voyages on the Avontuur, is titled “Ship Earth.” The planet, he writes, has something in common with a seagoing vessel. Earth is always at risk of a new emergency, and its inhabitants have little choice but to work together with finite resources. He quotes Ellen MacArthur, a British sailor who once set a world record for the fastest round-the-world voyage on a solo sailboat. “Your boat is your entire world,” MacArthur later said. “What we have out there is all we have. There is no more.” After retiring from sailing, in 2010, she created a foundation committed to creating a circular economy, which aims in part to eliminate waste and climate pollution.

De Beukelaer told me that when wind waylaid the Avontuur in the Gulf of Mexico, the crew agonized about dwindling supplies and looked for unconventional ways to use what they had. They tried reinforcing a sail with glue. They scoured the deck with a thermometer, looking for places where they might try solar cooking. When that failed, the bosun fashioned insulation pads for their cooking pots, which stretched out their limited supply of gas. At the end of their six-month voyage, the crew of the Avontuur published a joint statement. “We have learned—by stitching a patch on a torn sail, splicing together a frayed rope, being creative with limited resources—that nothing is ever truly broken,” they wrote. “Solutions and innovations abound when your whole world is contained within a steel hull.” ♦

More Science and Technology

Can we stop runaway A.I. ?

Saving the climate will depend on blue-collar workers. Can we train enough of them before time runs out ?

There are ways of controlling A.I.—but first we need to stop mythologizing it .

A security camera for the entire planet .

What’s the point of reading writing by humans ?

A heat shield for the most important ice on Earth .

The climate solutions we can’t live without .

Support The New Yorker’s award-winning journalism. Subscribe today .

Carbon Footprint

A carbon footprint is the total amount of greenhouse gases (including carbon dioxide) produced directly or indirectly by our activities and lifestyle. Learn how to calculate your boat’s carbon footprint, and ways to reduce and/or offset your impact.

Join Our Green Boating Community

What’s the Global Carbon Cycle?

Moderate levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) in our atmosphere are normal, as CO2 helps keep the planet warm and plays an integral role in many key biological processes, including photosynthesis. The earth naturally produces and processes CO2 in what is referred to as the Global Carbon Cycle. Human activities have altered this natural cycle by adding more CO2 to the atmosphere, and by affecting the ability of natural sources to remove it. The primary cause of increased CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere is due to the burning of fossil fuels (oil, coal and natural gas), as well as changes in land-use (deforestation).

The ocean plays a key role in keeping the carbon cycle in balance by absorbing excess CO2 from the atmosphere. When CO2 is absorbed by seawater, chemical reactions occur that increase the acidity of the water, a process known as ocean acidification. This increase in acidity will make it more difficult for corals to build or maintain skeletons, and for shellfish such as lobsters, scallops and clams to build shells.

Oceans also face elevated temperatures and rising sea levels due to the warming of the atmosphere.

Without conscious effort, CO2 concentrations will continue to rise in the atmosphere and our ocean ecosystems will suffer. We can take personal action to decrease CO2 emissions to protect our ocean.

What’s a carbon footprint?

A carbon footprint is a measure of the impact our activities have on the environment. It calculates the greenhouse gases we have, or are expected to produce in our activities, and measures them in pounds or tons of CO2. Personal carbon footprint emissions can come from direct sources such as driving your car or indirect sources such as the fuel burned to produce a product you’ve purchased. We can effectively lower our personal carbon footprint by voluntarily improving the energy efficiency in our homes, on our boats, and by purchasing local products and changing our consumption patterns.

What’s your boat’s carbon footprint?

Your boat’s carbon footprint is the emission of CO2 primarily from burning the fuel in your engine(s) and generator.

No two boats are the same and each will have a different footprint. The size and type of the engine(s), their age, the fuel type, your average cruising speed, the fuel efficiency and number of hours you use your boat all contribute.

As these factors are hard to quantify, the easiest route to estimating your boat’s footprint is by keeping track of your fuel usage.

How do you calculate your boat’s carbon footprint?

You can calculate your carbon footprint by determining the average number of gallons your engine(s) use per hour, then multiply this by the total number of hours you use your engine(s) during the season or year.

The key to lowering your boat’s carbon footprint is to decrease your fuel consumption. You will also save money – win win for the environment and your wallet! For tips on how, check out Reduce Fuel Usage and Renewable Energy .

How do you offset your carbon footprint:

Purchasing carbon offsets is one of the ways you can help address the imbalance that our daily lives have on our environment. A carbon offset is a reduction in emission of CO2 made in order to compensate for (or to offset) emissions made elsewhere.

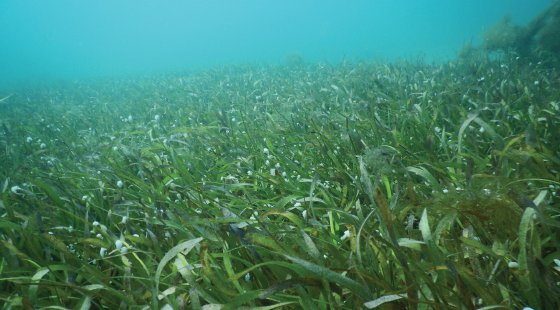

The Ocean Foundation’s Seagrass Grow offers the first carbon offset program where you can compensate for your impact with “blue carbon” through the planting of seagrass meadows.

Impressively, seagrass habitats are up to 45 times more effective than the most pristine Amazonian rainforest in their ability to absorb excess CO2 from the atmosphere and a single acre of seagrass may support as many as 40,000 fish, and 50 million small invertebrates ( Seagrass Grow ). Better yet, Seagrass Grow focuses their replanting efforts on areas that have been damaged by boat propellers and anchors.

Did you know?

- Seagrasses only occupy 0.1% of the seafloor, yet are responsible for 11%of the organic carbon buried in the ocean.

Sailors for the Sea Powered By Oceana 449 Thames Street, Unit 300D Newport, RI 02840 USA

Inquiries +1(401)-846-8900 [email protected]

OCEANA'S EFFICIENCY

BECOME A GREEN BOATER

Sign up today to get weekly updates and action alerts from sailors for the sea powered by oceana., show your support with a donation, help protect your passion and save what you love by making a tax-deductible donation today., quick links:.

Store Blog Clean Regattas KELP Financials Privacy Policy Revisit Consent Terms of Use Contact

Decarbonization of shipping: An ambitious global test bed for green ships sets sail

Shipping accounts for 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Image: Unsplash/Andy Li

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Dong Kwan Kim

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Supply Chain and Transport is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, supply chain and transport.

- Change is under way to decarbonize shipping, but the industry continues to face a wide range of challenges.

- Green ship technology is central to advancing decarbonization efforts, but demand for advanced vessels is insufficient.

- A newly-established shipping company powered by green ships will provide opportunities for innovation and collaboration.

With 90% of traded goods being transported across the ocean, the shipping industry stands at the heart of the global economy.

Although shipping is highly efficient in terms of CO2 emissions per cargo weight , the industry as a whole is a major contributor to the world’s carbon footprint, accounting for 3% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions . This is due to the sheer volume of movement and the industry’s heavy dependence on fossil fuels.

As pressure mounts to deliver measurable progress toward carbon neutrality, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) has revised its GHG emissions reduction strategy , pledging to reach net zero by or around 2050.

Have you read?

How can the shipping industry reduce emissions, shipping is targeting zero emissions. here’s how an industry coalition plans to help, here's how shipping can change course to hit emissions targets, davos 2024: who's coming and what to expect.

In line with this progression, an increasing number of large companies have been placing alternative-fuel ship orders . Additionally, more stringent measures such as the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) and FuelEU Maritime initiative are expected to lead to growing costs for heavy emitters.

At the same time, incentives like the US Inflation Reduction Act are generating opportunities to build and strengthen the value chain of clean energy sources, such as hydrogen, which will be crucial to powering carbon-free future vessels.

Why shipping is a hard-to-abate sector

Change is evidently under way, but it is not yet swift enough to meet net zero targets. A web of complexities including technical difficulties and costs associated with decarbonization mean the shipping industry remains a hard-to-abate sector.

Here are some of the main obstacles.

1. A lack of viable alternative fuels

Although many types of alternative fuels and powering mechanisms are being explored such as hydrogen, ammonia, methanol, biofuels, fuel cells and more, there is no one clear frontrunner in the race.

2. Demand for green ships is lacklustre

Building a new ship is a massive endeavour, requiring immense capital investment. Yet, these assets take roughly two to three years to build and last for two to three decades. Without clarity on how new ships will be fuelled, shipowners are hesitant to place orders for new advanced vessels.

3. Asset and infrastructure development is slow

With inadequate demand, shipbuilders and infrastructure developers are unable to advance new technologies and build infrastructure that can accommodate future-ready vessels.

4. Uncertainties in regulations

Although carbon emission regulations are advancing in regions such as the European Union (EU), they are loosely defined with many uncertainties around accountability.

The global nature of shipping necessitates a currently lacking unified industry effort to prevent emissions from merely shifting from regions with tight regulations to those with less stringent measures.

5. Too many stakeholders

For any given shipment, the parties involved easily span from the owner of goods (shipper) to the shipowner, ship operator, freight forwarder and, ultimately, the customer. Who should be accountable for the carbon emitted?

Questions like these have led to disputes between shipowners and traders , signalling the growing complexity behind regulatory enforcement and lack of clarity around roles and responsibilities.

How to bring about change in shipping

How can we bring about change in the face of such complexities? Breaking a gridlock of this nature requires a fundamentally different strategy – one that can create real change in one field and spark progress in others.

In the shipping industry, we can achieve a breakthrough by adopting a three-step approach:

1. Identify the catalyst for change

At Hanwha, we believe green ship technology is a central piece of the puzzle. Without it, decarbonization cannot take place at the requisite speed and scale. The fact that 85% of emissions come from a specific category of vessels – deep sea ships – gives the problem of decarbonization greater focus, making innovation in this area promising.

With a world-class shipbuilder, Hanwha Ocean, among our subsidiaries, we are dedicated to delivering disruptive, yet economically feasible, technical solutions in this field.

2. Innovate, test and repeat

To generate the necessary demand for the advancement of green ship technology, we have joined the World Economic Forum’s First Movers Coalition (FMC) and established a global shipping company, which will operate a new fleet of cutting-edge future-ready vessels.

With entirely new assets, the fleet will serve as a strong test bed for carbon-neutral and carbon-free vessels, lowering the emissions burden for traders and providing shipowners with increased flexibility to meet the diverse fuel requirements of their customers.

COP28: What is the First Movers Coalition and what has it achieved so far?

The advanced vessels will initially include ships that run on liquefied natural gas (LNG) and methanol and advance over time to those that run on ammonia, and hydrogen, which do not emit carbon when burnt as a fuel source.

We will also step up the development of ship digitalization, with the aim of powering vessels with fuel cells and electricity, mirroring the evolution from conventional cars to electric vehicles in the automobile industry.

3. Collaborate and build scale

Our membership with the FMC will pave the way for new partnerships and pilot programmes that enable collaboration with multiple stakeholders, including policy-makers, customers, research institutes and port authorities.

However, we can only build sustained momentum through mass adoption and commercialization of newly-developed technology, requiring a concerted effort between the public and private sectors as well as parties across the entire energy value chain.

This, coupled with clearly defined strong global regulations, will build an ecosystem for change, leading to the rapid scaling of green vessels to usher in a new era of global shipping.

The Global Rewiring report highlighted that collective thinking on global value chains is changing due to increasing disruptions driven by geopolitical tension, climate change, and technological shifts.

The World Economic Forum’s Centre for Advanced Manufacturing and Supply Chains is at the forefront of future-proofing the global manufacturing industry. It supports sustainable growth by fostering innovation and accelerating the adoption of inclusive technology.

Learn more about our impact:

- The Global Lighthouse Network : We have brought together 132 manufacturing factories from various industries who are applying advanced technologies to boost productivity, enabling them to scale and replicate innovations.

- Circular value chains : We actively support manufacturers in incubating new pilots that reinforce trust in circular value chains, such as authenticating fashion products in second-hand markets and exchanging CO2 footprint data across supply chains .

- Resiliency : In partnership with Kearney, we developed the Resiliency Compass to help guide companies in navigating supply chain disruptions and enhancing their resilience.

Want to know more about our centre’s impact or get involved? Contact us .

Big problems require bold solutions. The barriers to decarbonizing shipping are manifold, but a singular driving force can have a ripple effect, opening up new opportunities for many different parties.

Working together to uncover these novel growth drivers is what ultimately will help us turn the tide on emissions in the shipping industry.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing