Building, restoration, and repair with epoxy

How to Build Rudders & Centerboards

by Captain James R. Watson

When the centerboard of my Searunner trimaran broke in the middle of a windy race around the Black Hole, the question I kept asking was “Why now, after working fine all of this time, and when we were leading the race?”

“Guess it just wore out” was my excuse to myself. This centerboard was built of laminated layers of plywood, resulting in a thickness of 2″. It was then covered with two layers of 6-oz woven fiberglass fabric. It was a deep and wide board with a lot of area, and like any rudder or centerboard on a boat that is sailed hard, it was exposed to a fair amount of stress.

The answer to “Why now – while leading the race?” could have been fate. But there is a more scientific answer. Extensive laboratory testing at Gougeon Brothers, Inc. defines why the centerboard failed. Understanding why can help us design and construct components that will perform more efficiently and last much longer.

The plywood centerboard did, in fact, wear out – or more accurately – it failed from rolling shear fatigue. Fatigue cracks in a material result from repeated (cyclic) stress. Fatigue is a reality of all structures and materials and eventually culminates in structural failure. Repeated loading and unloading or even worse, loading one way and then the other (reverse axial), rapidly reduces a material’s physical integrity and accelerates degradation. The higher the load is as a percentage of the material’s ultimate strength, the more rapid is the deterioration.

Some materials have a greater fatigue life than others. Ounce per ounce, wood is capable of operating at a much higher percentage of its ultimate stress level than most other materials. That is why such wonderfully efficient structures can be built with wood. However, plywood is not a good choice for cantilevered structures such as rudder blades and centerboards. This is because plywood is susceptible to rolling shear, shearing forces that roll the structural fibers across the grain. Plywood’s unidirectional wood fibers are laid in alternating layers, approximately half of them are oriented 90 degrees to the axis of the loads. Like a bundle of soda straws, which resist bending moments quite well one way, they simply lack cross-grain strength laterally and can roll against one another and fail under relatively low stress, especially in a cyclic environment. Therefore, when anticipated loads are primarily unidirectional, it is ideal to use a material with good unidirectional strength. Since only half of the plywood’s wood fiber is used to advantage, a plywood rudder blade or centerboard going from tack to tack (reverse axial loads) will fatigue much more rapidly than one built as described in this article.

If you were to look at the end of the board, say a fish’s view of a centerboard or rudder blade, you’d view its cross-section. A section that has a faired airfoil shape is preferred over one that is flat with parallel sides. This is because the airfoil shape produces lift when moving through the water, thereby counteracting the sideward forces exerted by the sail rig. A flat section produces less lift and at a great expense of drag, slowing the boat and making it more difficult to steer.

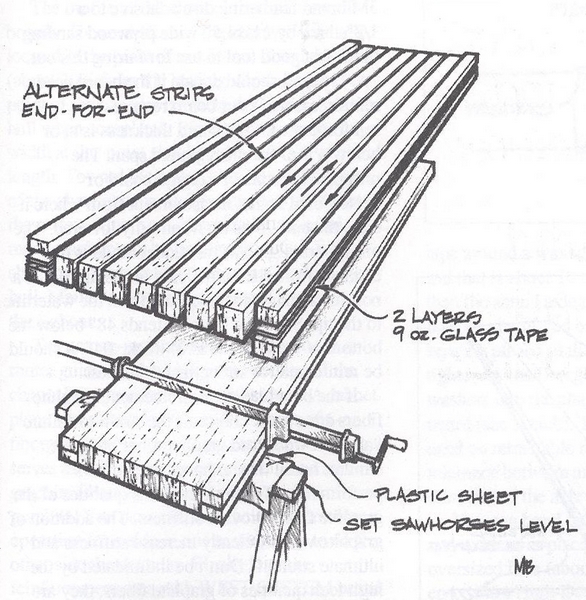

“Turn every other ripping end-for-end to neutralize the effects of any grain that does not run exactly parallel to the blank, and to reduce tendencies to twist. Rotate the rippings 90 degrees to expose the vertical grain and to permit easier shaping with a plane.

The selection of a proper camber and section can be a subject of great theoretical debate. One can become intimidated with technical terms such as thickness distribution, Reynolds number, boundary layer, and so on. These terms do relate to the subject, however, for the builder/sailor whose boat floats forlornly in need of a rudder blade the following will do just fine. In fact, the best designers and builders will be hard-pressed to do better.

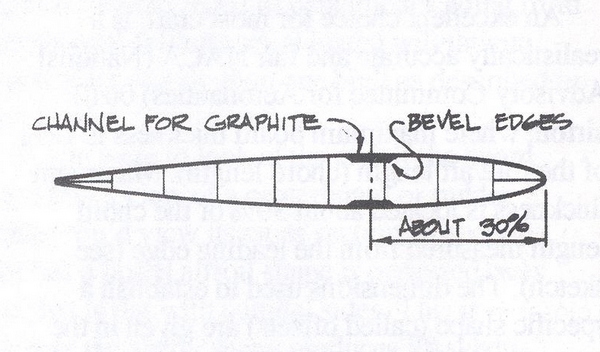

An excellent choice for most craft is a realistically accurate and fair NACA (National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics) 0012 airfoil, where maximum board thickness is 12% of the fore/aft length (chord length). Maximum thickness is located about 30% of the chord length measured from the leading edge (see sketch). The dimensions used to establish a specific shape (called offsets) are given in the appendix of Abbott & Doenhoff’s The Theory of Wing Sections. You’ll also find further information in my article How to loft Airfoil Sections.

From offsets make a good drawing of half the section on transfer paper.

Western red cedar and redwood are good choices of wood to use for rudder blades and centerboards for boats up to 25 feet. Both of these woods bond very well are generally clear and straight-grained, have good dimensional stability, are easily worked and affordable. Cedar is just a little heavier than the foams used for rudders, is much stiffer, and has far greater shear strength values. On larger craft, a higher-density material like African mahogany is a better choice. Oak is not a good choice.

Buy flat-grained 2’x6″s or 2’x8″s, and then rip them to the designed board thickness. Turn every other ripping end-for-end to neutralize the effects of any grain that does not run exactly parallel to the blank, and to reduce tendencies to warp or twist (see sketch). Rotating the rippings 90 degrees to expose vertical grain will permit easier shaping with a plane. The last trick is to rip the end pieces of the nose and tail in half. Bonding with a couple of layers of glass tape between keeps the fine edge of the tail from splitting too easily and offers a precise centerline.

Bond the ripping with a slurry of epoxy and 404 High-Density filler. Plastic strips prevent inadvertent bonding to leveled sawhorses (see sketch). With both sawhorses leveled, you’re positive no twist exists in the laminated blank. Bar clamps should be snugged until excess glue squeezes from the joints. Over tightening only stresses joints and tends to squeeze all the adhesive from them. When the laminate is cured, a light planing to clean the surfaces is all that is needed before shaping begins.

Centerboards and rudder blades are often overlooked components that are vital to a boat’s performance.

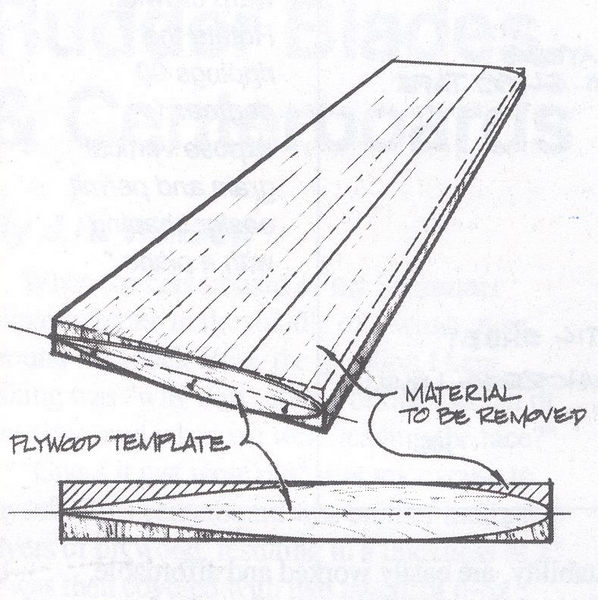

First, tack the 1/8″-thick plywood template that describes the cross-section shape to the blank’s ends. This is sawn from the impression made when traced with the transfer paper you originally drew it on. The key to producing an accurate and symmetrical board is maintaining a systematic removal of material from one side, then from the other. To do this, mark the shape to be removed, stick to straight-line shapes (see sketch). Use a smoothing plane to remove the wood.

After planing to the guidelines on one side, flip the blank over and plane the same shape on the other side. The procedure is similar to producing a round shape from a square by first forming an octagon, and then flattening the resulting eight corners to produce a 16-sided shape and refining that until very minute flat surfaces exist. Fifty-grit sandpaper bonded with 3M brand feathering disc adhesive to a 1/2″-thick by 11’x4.5″-wide plywood sanding block is a good tool to use for fairing this out.

Now you should decide if the board needs reinforcement. Your board requires reinforcement if the chord thickness is at or below 4% of the unsupported span. The unsupported span of a daggerboard or centerboard is that measurement from where it exits the hull, to its tip when fully lowered. The unsupported span of the rudder blade is the distance from the rudder case to the tip. If it is a non-retracting blade, measure from the waterline to the tip. So, if the board extends 48″ below the bottom of the hull and is 2″ thick, .04″, it should be reinforced for strength and stiffness.

If the board needs reinforcement, graphite fibers are a good choice as the strain-to-failure values of wood and graphite fiber are quite similar, hence they enhance each other’s performance. The high-modulus qualities of the graphite fibers provide stiffness. The addition of graphite will efficiently increase stiffness and ultimate strength. Don’t be intimidated by the high-tech qualities of graphite fibers, they are easy to work with.

The amount of reinforcement needed is usually figured at 10% chord thickness. Using the same board for our example, the board is 2″ thick, then 10% equals .20″ total reinforcement, .10″ per side. Graphite fiber tows are .01″ thick, so 10 tows per side should give the necessary reinforcement to do the job.

The graphite fibers will be laid into a channel routed into the shaped centerboard.

The graphite fibers will be laid into a channel that is routed into the shaped board (see sketch). The specific depth of the channel is determined by the above rule. Make the channel a little deeper than what’s required (1/16″) so you won’t be sanding the graphite fibers.

The profile of the channel is similar on all boards. The centerline of the channel is usually located at the point of maximum chord thickness (about 30% from the leading edge). The widest point of the channel is where the board exits the hull when completely lowered. The channel width at this point should be about 16% of chord length. Toward the ends of the board, the width of the channel narrows by about one-third that of the widest dimension. Keeping this in mind, more graphite can be laid in that area, a little above and more below that point that exits the hull. Maintain a consistent channel depth throughout.

Take a one-inch-square stick to serve as a router guide. It’s best to bevel the edge of the channel to reduce stress concentration. A rabbet plane serves best for this task. A layer of 6-oz fiberglass cloth is laid in the channel first (this serves as an interface between the wood and graphite fiber), followed by the schedule of graphite. You can complete the entire bonding operation for a side in one session. Try to do the other side the next day. Finally, fair the reinforcement area with WEST SYSTEM brand epoxy and a low-density filler.

A layer of 6-oz woven-glass fabric should then be bonded to the faired board to improve the cross-grain strength and abrasion resistance. The radius of the leading edge should be about a 1% radius of the chord length, and may not permit the fiberglass fabric to lie flat around the radius. In that event, cut a strip of woven glass fabric on the bias (which will lie around a tighter radius) and bond it around the leading edge.

It is better to leave the trailing edge slightly squared rather than razor-sharp. This will cause less drag and the centerboard will be less vulnerable to damage. Flatten the trailing edge to 1/16 or 1/8 of an inch on small boards, and closer to 1/4 of an inch on larger boards.

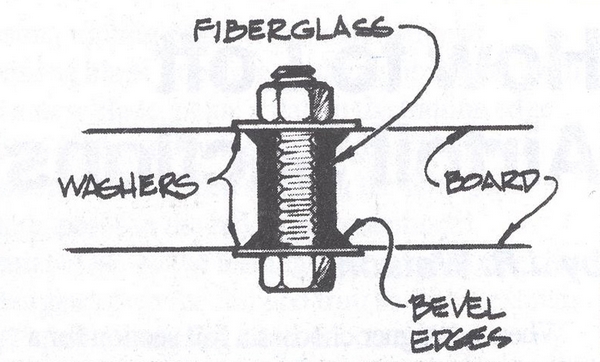

Any board, no matter how stiff, will deflect. To prevent the axle hole that the centerboard pivots on from binding when deflection occurs, make the hole somewhat larger than the pin diameter. The perimeter of the axle hole should be thoroughly protected with fiberglass, as exposed end grain can absorb moisture.

To prevent the axle hole from binding when deflection occurs, make the hole a little larger than the pin diameter.

Abrasion of the axle against the axle hole dictates that you should bond fiberglass into the hole’s perimeter. To do that, wrap fiberglass tape around a waxed (use auto paste wax) metal rod that is about 10 to 15% larger in diameter than the actual axle pin. The hole should be heavily chamfered on each side, so when the wet layup is placed in the hole and the nuts tightened, the fiberglass is pressed by the large washers into the chamfers on both sides of the board (see sketch). The same procedure may be used on retractable rudder blades, but the tolerance between axle hole diameter and the diameter of the axle pin should be closer.

You can bond control lines for centerboards and rudders-in-place by wetting a slightly oversized hole (about 1.5″ to 2″ deep) with epoxy/404 High-Density filler mixture. It helps to mark the hole’s depth on the rope with vinyl electricians tape to serve as a guide. Then, after soaking that end of the rope to be bonded in epoxy for a minute or so, shove it in the full depth of the hole.

Centerboards and rudder blades are often overlooked components that are of vital importance to a boat’s performance. Built correctly, they will reliably operate with the efficiency of a fish’s fin, and you should note a measurable improvement in the quality of pointing and steering of your windship.

References:

1. Jozset Bodig, Ph.D., Benjamin A Jayne Ph.D., Mechanics of Wood and Wood Composites 2. Johnston, Ken, Some Thoughts on Rudder Sections , Multihulls Magazine (Jan/Feb 1980) 3. Eck Bransford, Everything You Ever Wanted To Know About 505 Fins 4. Lindsay, Mark, Centerboards and Rudders , Yacht Racing/Cruising Magazine (April 1981) 5. Abbott and Doenhoff, Theory of Wing Sections, Dover Publications, Inc. New York (1959) 6. Captain James R. Watson, How to Loft Airfoil Sections , Epoxyworks 1 (Fall 1992)

How to Build a Sailboat Rudder From Scratch

Introduction: How to Build a Sailboat Rudder From Scratch

Step 1: Previous Rudder

Step 2: Rebuild

Step 3: Sanding

Step 4: Fiberglass Layup

Step 5: First Layer and Sanding

Step 6: Additional Layers and Difficult Spots

Step 7: Notes of Caution

Step 8: Hardware Holes

Step 9: Painting

Step 10: The End!

- New Sailboats

- Sailboats 21-30ft

- Sailboats 31-35ft

- Sailboats 36-40ft

- Sailboats Over 40ft

- Sailboats Under 21feet

- used_sailboats

- Apps and Computer Programs

- Communications

- Fishfinders

- Handheld Electronics

- Plotters MFDS Rradar

- Wind, Speed & Depth Instruments

- Anchoring Mooring

- Running Rigging

- Sails Canvas

- Standing Rigging

- Diesel Engines

- Off Grid Energy

- Cleaning Waxing

- DIY Projects

- Repair, Tools & Materials

- Spare Parts

- Tools & Gadgets

- Cabin Comfort

- Ventilation

- Footwear Apparel

- Foul Weather Gear

- Mailport & PS Advisor

- Inside Practical Sailor Blog

- Activate My Web Access

- Reset Password

- Customer Service

- Free Newsletter

Blue Jacket 40 Used Boat Review

Catalina 270 vs. The Beneteau First 265 Used Boat Match-Up

Ericson 41 Used Boat Review

Mason 33 Used Boat Review

How to Create a Bullet-Proof VHF/SSB Backup

Tips From A First “Sail” on the ICW

Tillerpilot Tips and Safety Cautions

Best Crimpers and Strippers for Fixing Marine Electrical Connectors

Polyester vs. Nylon Rode

Getting the Most Out of Older Sails

How (Not) to Tie Your Boat to a Dock

Stopping Mainsheet Twist

Fuel Lift Pump: Easy DIY Diesel Fuel System Diagnostic and Repair

Ensuring Safe Shorepower

Sinking? Check Your Stuffing Box

What Do You Do With Old Fiberglass Boats?

Boat Repairs for the Technically Illiterate

Boat Maintenance for the Technically Illiterate

Whats the Best Way to Restore Clear Plastic Windows?

Stopping Holding-tank Odors

Giving Bugs the Big Goodbye

Galley Gadgets for the Cruising Sailor

The Rain Catcher’s Guide

Sailing Gear for Kids

What’s the Best Sunscreen?

UV Clothing: Is It Worth the Hype?

Preparing Yourself for Solo Sailing

R. Tucker Thompson Tall Ship Youth Voyage

On Watch: This 60-Year-Old Hinckley Pilot 35 is Also a Working…

On Watch: America’s Cup

On Watch: All Eyes on Europe Sail Racing

Dear Readers

- Boat Maintenance

Building a Faster Rudder

Boost performance with a bit of fairing and better balanced helm..

We’re cruisers not racers. We like sailing efficiently, but we’re more concerned with safety and good handling than squeezing out the last fraction of a knot. Heck, we’ve got a dinghy on davits, placemats under our dishes, and a print library on the shelf. So why worry about perfection below the waterline?

The reason is handling. A boat with poorly trimmed sails and a crudely finished rudder will miss tacks and roll like a drunkard downwind when the waves are up. On the other hand, a rudder that is properly tuned will agilely swing the boat through tacks even in rough weather, and provide secure steering that helps prevents broaching when things get rolly. The difference in maximum available turning force between a smooth, properly fitted rudder and the same rudder with a rough finish and poor fit can be as much as 50% in some circumstances, and those are circumstances when you need it the most. It’s not about speed, it’s about control.

It Must Be Smooth

Smooth is fast. That’s obvious. But it makes an even bigger difference with steering. Like sails, only half of rudder force comes from water deflected by the front side of the blade. The rest results from water being pulled around the backside as attached flow. How well that flow stays attached is related to the shape of the blade, which we can’t easily change, and to the surface finish of the blade, which we can.

Remember the school experiment, where you place a spoon in a stream of water and watched how the water would cling to the backside of the spoon? Now, try the experiment again as a grown-up, but with a different set of materials.

Try this with a piece of wood that is smooth and one that is very rough; the water will cling to the smooth surface at a greater angle than the rough surface. Try piece of smooth fiberglass or gelcoat; the water will cling even better because the surface is smoother. Try a silicone rubber spatula from the kitchen. Strangely, even though the surface is quite smooth, the water doesn’t cling well at all. We’ll come back to that.

Investigators have explored this in a practical way, dragging rudders through the water in long test tanks (US Navy) and behind powerboats.

If we are trying to climb to windward, it’s nice to get as much lift out of the rudder as practical, before drag becomes too great or before it begins to stall with normal steering adjustments. If the boat has an efficient keel and the leeway angle is only a few degrees, the rudder can beneficially operate at a 4-6 degree angle. The total angle of attack for the rudder will be less than 10 degrees, drag will be low, and pointing will benefit from the added lift. If the boat is a higher leeway design—shoal draft keels and cruising catamarans come to mind—then the rudder angle must stay relatively low to avoid the total angle (leeway + rudder angle) of the rudder from exceeding 10 degrees. That said, boats with truly inefficient keels but large rudders (catamarans have two—they both count if it is not a hull-flying design) can sometimes benefit from total angles slightly greater than 10 degrees—they need lift anywhere they can get it.

How can you monitor the rudder angle? If the boat is tiller steered, the tiller will be about 0.6 inches off center for every degree or rudder angle, for every 3 feet of tiller length. In other words, the 36-inch tiller should not be more than about 2 inches off the center line. If the boat is wheel steered, next time the boat is out of the water, measure the rudder angle with the wheel hard over. Count the number of turns of the wheel it takes to move the rudder from centered to rudder hard over, and measure the wheel diameter. Mark the top of the rim of the wheel when the boat is traveling straight, preferably coasting without current and no sails or engine to create leeway.

The rim of the wheel will move (diameter x 3.146 x number of turns)/(degrees rudder angle at hard over) for each degree of rudder angle. Keep this in the range of 2-6 degrees when hard on the wind, as appropriate to your boat. It will typically be on the order of 4-10 inches at the steering wheel rim. A ring of tape at 6 degrees can help.

How do we minimize rudder angle while maintaining a straight course? Trimming the jib in little tighter or letting the mainsheet or traveler out a little will reduce pressure on the rudder and reduce the angle. Some boats actually sail to weather faster and higher, and with better rudder angles, by lowering the traveler a few inches below the center line.

On the other hand, tightening the mainsheet and bringing the traveler up, even slightly above the center line on some boats, will increase the pressure and lift.

Much depends on the course, the sails set, the rig, the position of the keel, the wind, and the sea state. Ultimately, some combination of small adjustments should bring the rudder angle into the appropriate range. Too much rudder angle and you are just fighting yourself.

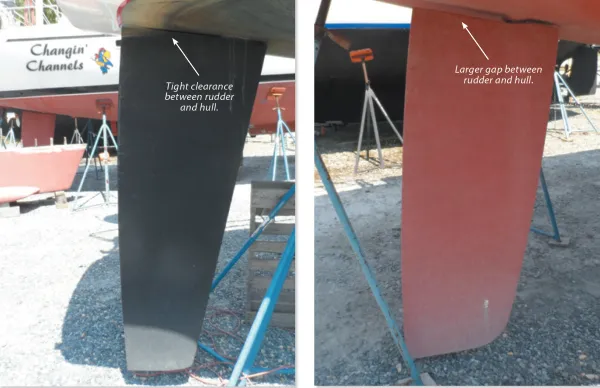

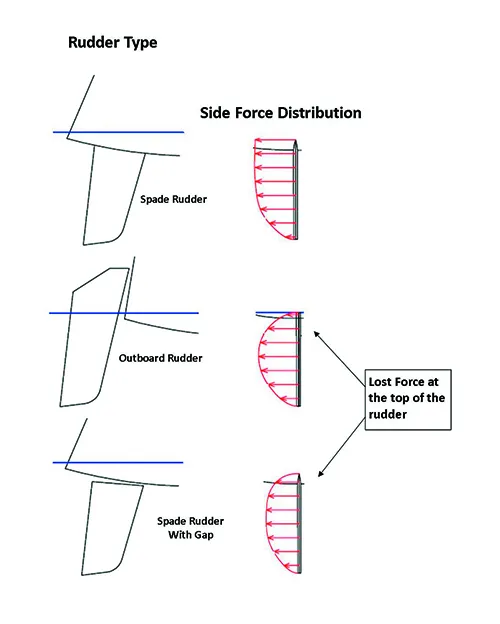

- Turn this rudder just 10 degrees and the end plate is lost, reducing the amount of lift generated.

- This rudder might as well be transom hung, the way that the end cap just disappears.

- Stern-hung rudders, and spade rudders with large gaps between the hull and the top of the rudder will lose their lift at the “tip” of the blade near the surface.

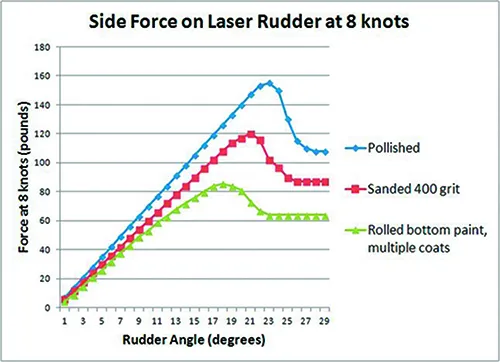

Surface roughness affects the lift from the rudder in two ways. A rougher surface has slightly lower lift through the entire range of angles, the result of a turbulent boundary layer instead of smooth flow over the entire surface. More dramatically, rougher blades stall at lower angles and stall more completely. The difference between a faired rudder with a polished finish and a rudder carrying a 10-year accumulation of rolled-on antifouling paint can be as much is 35 percent (see “Rudder Savvy to Boost Boat Performance,” above).

What can we do? If your rudder is a lift up type, don’t use bottom paint. Fair the blade within an inch of its life and lay on a gloss topside paint as smoothly as possible, sanding between coats. If you use a brush, stroke the brush parallel to the waterline, not along the length of the blade.

Which is faster, a gloss finish or one that has been dulled with 1000 grit sandpaper? Opinions go both ways, and we believe it may depend on the exact nature of the paint, which leads to the question, “Should we wax the blade?” The answer is a resounding, no.

Wax is a hydrophobic (readily beads water), like the silicone rubber spatula you tested, and as a result, water doesn’t always cling as well. Thus, whether the paint should be deglossed or not depends on the chemistry of the paint, but in all cases the final sanding should be 1000 grit or finer.

If the rudder stays in the water, antifouling paint is required. Sand the prior coat perfectly smooth. There should be no evidence of chips, runners, or any irregularity at all. Using a mohair roller, lay the paint on thin, and apply multiple coats to withstand the scrubbing you will give your rudder from time to time.

Even if you use soft paint on the rest of the boat, consider hard paint for the rudder. Sure, it will build up and you will have to sand it off periodically, but the rudder is small and no part of your boat is more critical to good handling. Take the time to maintain it as a perfect airfoil.

Close the Gap

Ever notice the little winglets on the tips of certain airplanes? As we know, those are intended to reduce losses off the tip of the wing. The alternatives are slightly longer wings or slightly lower efficiency. At the fuselage end of the wing, of course, there is no such loss because the fuselage serves as an end plate. The same is true with your rudder.

There’s not much you can do about losses from the tip; making the rudder longer will increase the chance of grounding and increase stress on the rudder, rudder shaft, and bearings. Designers have experimented with winglets, but they the catch weeds and the up-and-down motion of the transom makes them inefficient. However, we can improve the end plate effect of the hull by minimizing the gap between the hull and the rudder.

In principle it should be a close fit, but in practice the gap is most often wide enough to catch a rope. Just how much efficiency is lost by gap of a few inches? The answer is quite a lot. A gap of just an inch can reduce lift by as much as 10-20 percent, depending on the size and shape of the rudder and the speed. A gap of 1-2 mm is quite efficient, but normal flexing of the rudder shaft may lead to rubbing.

If the gap is tight, the slightest bend from impact with a submerged log can cause jamming and loss of steering, though in my experience once the impact is sufficient to bend the shaft, a small difference in clearance is unlikely to make much difference; the shaft will bend until the rudder strikes the hull. Just how tight is practical depends on the type of construction, fitting accuracy, and how conservative the designer was in their engineering.

Carbon shafts, tubular shafts, and rudders with skegs flex less, while solid shafts generally flex more, all things being equal. Normally a clearance of about 1/4-inch per foot of rudder cord is practical, and performance-oriented boats often aim for much less. If you can reach your fingers through, that’s way too much. Hopefully the hull is relatively flat above the rudder so that the gap does not increase too much with rudder angle.

Practical Sailor’s technical editor Drew Frye is the author of the books Keeping a Cruising Book for Peanuts and Rigging Modern Anchors. He blogs at his website, sail delmarva.blogspot.com .

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

22 comments.

How happy to see good technical information about the science of boat speed and control. This information is valuable to everyone, but the “mainly just cruising” cohort usually doesn’t get enough in an easily understandable form. I always suggest some club level racing as the best way to learning how to sail, but many prospective racers have been put off from the sport or haven’t had good opportunities to join the fleets. Technical seminars are generally either too advanced for beginners to understand properly, and the beginner classes are frequently too basic to inspre those who would benefit from a deeper knowledge base in the science of sailing. Good on you, Practical Sailor, for your technical stories hitting the “sweet spot,” getting this information to those we’ll benefit most.

Great article. How about considering modifying a rudder to make it a hydrodynamically balanced rudder. I did it to my boat and the difference is outstanding. If I remember correctly 7% of the rudder area is forward of pivot center. It is a skeg hung rudder that now turns like it’s a spade rudder.

I’m “skeg hung” also. Would you be so kind as to posting a link or providing info as to you accomplished this feat. Thanks!

A very clear explanation of some quite complicated hydrodynamics – thank you! I am surprised by the US Navy results showing benefit of sanding further than 400 grit. Most other experimental data suggest there is negligible advantage in going beyond about 360 grit. Is the original reference publicly available? On Michael Cotton’s comment, a couple of points: Firstly, the amount of balance (i.e how far back you put the stock in the blade) has no impact on the hydrodynamic performance of a spade rudder. What it does do is change the feel of the rudder; a well balanced rudder will be easier to use, thereby probably allowing the steerer to sail the boat better. For a skeg rudder, the hydrodynamic impact of changing the balance depends very much on how the skeg/blade combination is configured. Secondly, 7% of rudder area forward of the stock is not enough for most rudders. The position of the centre of pressure is dependent on a lot of factors (aspect ratio, rudder angle etc.), but it is usually at least 15% back from the leading edge on a spade rudder, more often 20%. A balance somewhere between 10% and 15% is likely to give just enough feel without too much weight. However, rudder balance is still a bit of a black art, it really does depend on the rudder geometry.

the statement that one doesn’t want a silicone/silane coated ( super-smooth, hydrophobic: silicone-silane is just the example I am choosing, since it is now in use as a massively-speeding hull-coating, ttbomk ), as it *induces* flow-separation…

looks to me like conflating cavitation with flow-separation.

People have no problem teflon/ptfe-coating aviation-wings, as a means of *preventing* flow-separation.

the super-slick shape of a Cirrus’s composite wing, if made super-smooth/polished & super-slippery, “air-phobic”, as it were, *improves* its performance, not detracts from it….

Flow is always 1. laminar, then 2. turbulent, then 3. flow-separation.

unless the angle-of-attack ( AoA ) is small-enough to prevent separation.

The Gentry Tufts System, for *seeing* when a separation-bubble begins, on a sail, is brilliant ( Arvel Gentry was a fluid dynamicist, & realized that once one has a *series* of tufts, from luff on back, about 1/4 up the luff, one can *see* the beginning of a flow-separation-bubble, & tune the sail to keep it *just*-beginning, because *that* is MAX lift. Wayback Machine has his site archived, btw )

The aircraft designer Jan Roskam wrote of a DC-10 crashing because pebbled-ice as thick as the grit on 40-grit sandpaper had formed on the upper wings…

obviously, engineered to require laminar, there, but having turbulent, cost all those lives.

iirc, it was Arvel Gentry, or “Principles of Yacht Design”, that stated it takes a ridge of about 0.1mm, only, to trip the flow around a mast from laminar to turbulent…

Given how barnacles & such are generally 100x or more as thick as that, when removed from a hull, I think laminar-flow is something that exists only for the 1st day or so after launching!

I now want to see experiment showing polar curves for rudders coated normally, uncoated, & ailicone-silane coated, to see if it is the coating that induces separation-bubbles, or if it is AoA exceeding functional angle, for that surface & foil,, while the boundary-layer is in specifically turbulent flow, as opposed to the ideal laminar, as aviation’s results indicate…

just an amateur student of naval-architecture & aircraft-design ( Daniel P. Raymer’s “Conceptual Aircraft Design” is *brilliant*, btw ), who happens to study this stuff autistically, as that is the only way to make my designs become absolutely-competent, is all…

I got a pearson and the rudder broke. Can I just replace with a outboard rudder mount it off set for room for outboard need info.

You could but it will not work very well. How badly it would perform is difficult to say. It might be just poor or disastrous. Things really need to be balanced on sail boats.

Polished rudders stall at low angles of attack and ask any hobie cat racer.

Pi is NOT 3.146

3.1416 maybe

Yup, 3.1416. Typo.

Before 2005 , when I fully retired and went cruising 10 months per year, I changed auto pilots, the hydraulics of which reduced the maximum rudder angle. “Someday” had always been difficult to steer in marinas, so I added 30% more rudder area to the Gulfstar 41′ by deepening and following the existing angles. (the pivot was unchanged, as all added area was aft of that.) It increased rudder effort noticeably, but not excessively, improved motor maneauvering and allowed being able to hold a close line better. Noticeably, it caused a lot more stalling of the rudder whenever it was turned very much. A recent tangle with a Guatemala fish net damaged the extension, which I had intended to be sacrificial. I cleaned up the separation somewhat, but have not replaced the extension. The boat again now requires more steering correction when heading at all upwind, but the rudder does not stall as easily.

This is not a scientific study, just my personal non-scientific observations. The added rudder area was quite low, and the fairing quality was…well! modest.

I’ve seen data suggesting ~ 400 grit is best, and I’ve seen data suggesting polished is best. They were both smart, respected guys that I would not second guess. My conclusion is that other factors, such as the specific foil profile and the type of coating, are involved. Let’s just agree that many layers of rolled bottom paint with a few lumps and chips is sub-optimal! We’re talking about cruising boats.

Thanks for great article. I’m convinced enough to go sand my bottom paint off the lifting rudder of my Dragonfly Tri.

Absolutely! No lifting rudder should have bottom paint. My Farrier rudder was sanded fair and painted with gloss white.

Dagger boards and center boards that retract still need antifouling, since they do not lift clear of the water, but because they are in a confined space with little oxygen or water flow, fouling is very limited. Because the space is tight and paint build-up can cause jamming, sand well and limit the number of coats. For my center board I go with two coats on the leading edge (exposed even when lifted) and one coat on the rest.

I do remember a comment directed to cruisers a few years back suggesting that a faster cruiser would be more likely to get out of the way of dirty weather, especially with modern forecasting. I reckoned that this concept would gain traction, but I haven’t seen it. Can anyone weigh in on this opinion?

I would agree ONLY for coastal crusing when a safe harbor is always no more than a day away. OR ocean racing where speed matters and the boat is kept light. We all know weather reports past 24hours are a guide not a guarantee. Once a storm is bearing down NO boat even a fast one is going it out run a storm. Also we sail on boats that need wind and it’s always a balance between a course between high pressure systems (doldrums) and low pressure systems (high likelyhood of a storm) so because we seek wind sometimes we get more then we want. Try and avoid that and you risk venturing too far into the high pressure system and NO wind. So yes weather forecasts can give you a 1-2 day weather window and a fast boat that can get the hell out of dodge and put a few miles between itself and the oncoming weather could avoid a storm. BUT we are usually not talking about a world ocean race boat vs an old full keel tank. We are talking a faster but still rather slow loaded down cruising boat. It may be only the difference of 7knot average vs 9 knots average. Even a faster cruiser/racer is not a stripped down Volvo series racer. And even those super fast ocean racers pushing the edge of technology get caught in storms and frankly I would not want to use one of those boats as my floating home on the water. They are a thrilling ride but far from comfortable. And they STILL can’t sail fast enough to out run a storm and guarantee you you will never have to sail in big waves and high winds. There is not a cruising SAIL boat that is as fast as a center console fishing boat with 1200hp in outboards on the back and guess what when a squall is coming even they get caught and can’t out run it. And no it’s not a hurricane and it won’t last long but it’s enough when it hits you if your on a light boat over canvased because trying to outrun the oncoming squall it’s enough to get scary. And then there is comfort. Even when there is no storm near you the swell from a storm hundreds of miles away can make for a uncomfortable ride in a boat designed to go fast vs a heavy displacement boat that just pushes threw waves and Has the tonnage not to get knock around. So much of this article screams weekend coastal sailing as even a week on anchor all that work to smooth your rudder will be canceled out by bottom growth todays antifoul paints don’t work as good as the older but far more toxic formulas so even the most meticulously cleaned cruising boat picks up growth ya you can dive and clean it regularly but I often it’s like Sisyphus pushing that rock up the hill. And besides if your sailing on a fullkeel with a keel hung rudder most of this is mute. yes a clean smooth bottom makes a difference on any boat but it’s the full keel and its tendency to track straight the over all weight and momentom of the boat it’s not fast and never will be but they can maintain their hull speed and track a comfortable ride threw chop and be unaffected by the swell. I’ll take a old full keel boat with a protected rudder I know is very unlikely to ever hit something to bend it or loose my rudder ever over a spade rudder or even worse duel rudders both hung exposed with a long but thin bolted on keel that if you hit a coral head means a haul out to inspect it as it more then likely cause a lot of expensive damage. And if not fixed right could lead to a future disaster (Cheeki Rafiki).

As interesting as the article reads, I wonder how it helps a prospective buyer of a used boat. Pictures will not do, and neither will taking several boats out of the water to examine them; it’s too expensive. It would be more helpful to indicate which boat manufacturers have the type of rudder the author recommends. After all, the buyer usually cannot be expected to change a rudder prior to buying it; it is also expensive. By the way, these types of very sophisticated articles are seen when it comes to hulls, keels, or rigging but without identifying the boats that carry the wrong equipment. If a specific rudder or keel configuration is not the proper one for efficient sailing, the author ought to state which boats carry the proper ones so that the buyer will concentrate on the whole (the boat) rather than the part.

I was describing the opportunity to improve the existing rudder. As I think back, I have modified the rudder of every boat I have owned in order to improve efficiency. The first two got small changes in balance and improved trailing edge sharpness. On the third I tightened the the hull clearance and changed the section. On my current boat I adding an anti-ventilation fence to improve high speed handling. https://4.bp.blogspot.com/-2ZGPzKdj_tE/WyF9G2mHtLI/AAAAAAAAOwE/r6zgQEr4vkcDB4ciMLcgboFdazDAseDBgCLcBGAs/s1600/ian%2Brudder%2Bfence.jpg None of these tasks was overly difficult, and none was undertaken until I had sailed the boat for a season and learned what balance she liked and noted her habits.

For me, I buy a boat based on reputation, a test sail, and in most cases, a survey. As you imply, it is the whole boat you are buying. Does it have good bones? Do you feel happy at the helm? Then comes the fine tuning. I’ve been told that I sell a boat when I run out of things to tweak.

wow, so now case reports/medical reports/evidence don’t count as “evidence”, but certain remedies, even if they are cited in medical journals but do not work in the real world, count as evidence to you?? Maybe we need to redefine evidence based on your philosophies.Anyway, i’ve wasted enough time here. goodbye.

Weight 2.5 tonnes

Do you have any articles on the ideal cross section shape for an outboard rudder mounted 50mm from the transom vertically The yacht is a 26 ft trailer sailer weight 2.5 tonnes

The most common choice would be NACA 0012. http://airfoiltools.com/airfoil/details?airfoil=n0012-il

There are many ways to build a rudder, including laminated solid rot-resistant wood and fiber glass covered foam with a metal armature core. For the DIY, laminated wood is probably the most practical.

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Log in to leave a comment

Latest Videos

Cabo Rico 34 Boat Review

Super Shallow Draft Sailboat: The Leeboard Sharpie

Hans Christian 41T – Boat Review

Seven dead after superyacht sinks off Sicily. Was the crew at...

Latest sailboat review.

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- Online Account Activation

- Privacy Manager

How To Make A Rudder For A Sailboat

Key Takeaways:

- Choose a strong and durable wood for the rudder blade, such as oak or mahogany.

- Consider the shape of the rudder blade: flat blades provide more lift, while curved blades reduce drag.

- Use lightweight materials like fiberglass or carbon fiber for the rudder frame to provide strength without adding unnecessary weight.

- Test and fine-tune the rudder in different weather conditions to optimize handling and maneuverability.

If you’re itching for the freedom of the open water, why not make your own rudder for a sailboat? In this article, we’ll show you how to select the right materials, design the perfect rudder, and build it from scratch.

With a little effort and some handy tools, you’ll be steering your sailboat with ease in no time. So, get ready to take control and experience the true joy of sailing on your own terms.

Table of Contents

Selecting the Right Materials

You should start by gathering the necessary materials for making a rudder for your sailboat.

As someone who desires freedom, it’s essential to choose the right materials that will withstand the forces of the wind and waves. Firstly, you’ll need a strong and durable piece of wood for the rudder blade. Look for a hardwood like oak or mahogany that can withstand the harsh marine environment.

You’ll need stainless steel or brass hardware to attach the rudder to the boat. These materials are corrosion-resistant and will ensure the rudder stays securely in place. Additionally, you’ll need screws or bolts to fasten everything together . Make sure to choose the appropriate size and length for your specific sailboat.

You’ll need a high-quality marine-grade varnish or paint to protect the wood and prevent water damage. This won’t only add a touch of style to your rudder but also prolong its lifespan.

Check this Youtube Video that might be helpful:

Designing Your Rudder

When designing your rudder, carefully consider its shape and size for optimal performance on the water. Y our rudder plays a crucial role in maneuvering your sailboat, so it’s important to get it right.

Start by thinking about the shape of your rudder blade. A flat blade will provide more lift, allowing for better control and responsiveness. On the other hand, a curved blade will reduce drag, increasing your boat’s speed. It’s all about finding the right balance that suits your needs.

Consider the size of your rudder. A larger rudder will provide more control and stability, especially in strong winds and rough waters. However, keep in mind that a larger rudder also means more drag, which can slow you down. Again, finding the right balance is key.

Take into account the material you’ll use for your rudder. Lightweight materials such as fiberglass or carbon fiber are popular choices as they offer strength without adding unnecessary weight. Remember, the lighter your rudder, the less drag it will create.

Overall, designing your rudder is a personal process that requires careful consideration of shape, size, and material. Take the time to experiment and find what works best for you and your sailboat.

Enjoy the freedom of customizing your rudder for optimal performance on the open waters.

Building the Rudder Frame

Once you have designed your rudder, it’s time to start building the rudder frame. Building the frame for your sailboat’s rudder is an exciting step towards bringing your vision to life.

Here are three key steps to help you construct a sturdy and reliable rudder frame:

- Gather the materials : Start by gathering the necessary materials, such as marine-grade plywood, fiberglass cloth, epoxy resin, and stainless steel screws. Ensure that you choose high-quality materials that can withstand the harsh marine environment and provide long-lasting durability.

- Cutting the plywood : Using the measurements from your rudder design, carefully cut the marine-grade plywood into the required shape and size for your rudder frame. Make sure to be precise and take your time to achieve accurate cuts.

- Assembling the frame : Once the plywood pieces are cut, assemble them according to your design. Apply epoxy resin to the edges of the plywood and secure them together with stainless steel screws. Reinforce the joints with fiberglass cloth and additional layers of epoxy resin for added strength.

Attaching the Rudder Blade

To attach the rudder blade, you’ll need to follow these steps carefully.

Ensure that the rudder blade is aligned properly with the rudder frame. Take the blade and slide it into the rudder head, making sure it fits snugly.

Secure the blade in place by inserting the rudder pin through the holes in the rudder head and blade. This will prevent the blade from coming loose while you’re sailing. Once the rudder pin is in place, use a cotter pin or a hairpin clip to secure it. Make sure it goes through the hole in the rudder pin, preventing it from slipping out. This will ensure that the rudder blade stays attached during your sail.

After securing the rudder blade, give it a test by moving it from side to side. It should move smoothly without any resistance. If you notice any stiffness or difficulty in movement, check if the blade is properly aligned or if there are any obstructions that need to be addressed.

Testing and Fine-Tuning Your Rudder

Before you begin sailing, you should test and fine-tune your rudder to ensure optimal performance on the water. Here are three important steps to follow:

- Test in calm waters : Find a calm and protected area where you can safely test your rudder. This will allow you to focus solely on the rudder’s performance without any external factors affecting your observations. Start by sailing in a straight line and make note of any deviations or difficulties in steering. Pay attention to how the rudder responds to your inputs and make adjustments accordingly.

- Adjust the rudder angle : Fine-tuning the rudder angle can greatly impact the handling of your sailboat. Experiment with small adjustments and observe the changes in how the boat responds. A slight change in the angle can make a significant difference in maneuverability and overall performance. Keep testing and adjusting until you find the sweet spot that allows for smooth and effortless steering.

- Consider weather conditions : Remember that weather conditions can greatly affect the performance of your rudder. Test your rudder in different wind speeds and directions to understand how it responds in various scenarios. This will help you anticipate how your sailboat will handle in different weather conditions and make necessary adjustments to optimize your sailing experience.

What Are Sailboat Rudders Made Of

Ever wondered what keeps your sailboat steering straight, slicing through those waves like a hot knife through butter? Well, that’s all thanks to your rudder, the unsung hero of your seafaring adventures. A sailboat without a rudder is like a kite without a string – sure, it’ll still move, but good luck controlling where it goes!

But what are these crucial pieces of marine machinery made of, you ask? Good question! Sailboat rudders are crafted from a variety of materials, each with its own unique set of properties. So, let’s dive in and take a look at some of the most common materials used in rudder construction:

- Fiberglass: Highly durable and resistant to corrosion, fiberglass is a top choice for rudder construction. Often, it’s used in a sandwich-like structure with a foam or honeycomb core to increase stiffness and decrease weight.

- Wood: Traditional and still used in some applications, wood offers a natural aesthetic and is relatively easy to work with. Typically, it’s sealed with varnish or epoxy to make it more durable and water-resistant.

- Metal: Materials like stainless steel or bronze are sometimes used for rudders, especially on older or larger boats. Metal is extremely durable but can be prone to corrosion, especially in saltwater environments.

- Carbon Fiber: Used in high-performance and racing sailboats, carbon fiber is extremely strong and light. It’s also pretty pricey, so it’s not often seen in your everyday cruising sailboat.

- Plastic: Yes, you read that right. Some smaller or more affordable sailboats use plastic rudders. While they’re not as durable or efficient as other materials, they’re easy to replace and quite cost-effective.

So there you have it — a behind-the-scenes look at what’s keeping your sailboat on course.

Fiberglass is one of the most popular materials used to make sailboat rudders. It is lightweight , strong , and can be easily molded into a variety of shapes and sizes . It also resists corrosion and does not require much maintenance . The disadvantage of fiber glass is that it is not as strong as metal , so it may need to be reinforced with additional material such as carbon fiber or Kev lar .

Wood is another material commonly used to make sailboat rudders. It is strong and durable, and can be easily shaped into the desired design. Wood can be susceptible to rot and decay, so it needs to be properly sealed and maintained.

Metal is the most durable material used to make sailboat rudders. It is strong and can withstand the forces of the sea. Metal is also heavier than other materials, and can be difficult to shape into the desired design and the task of how to make a rudder for a sailboat might be more difficult.

What is the best wood for rudder

Oak is an ideal wood for r udd ers due to its strength and durability . Oak is also resistant to water and humidity and can hold up to harsh weather conditions . In addition , oak is fairly inexpensive compared to other hard woods , making it a cost - effective material for rud der construction . It is very good for sunfish boats and other light sailing vehicles.

What You Will Need

The most important materials that you will need to make a sail boat rud der are wood , metal , and fiber glass . To build a rudder for a boat, you will need a piece of wood (or other material like fiberglass or metal) cut to the desired size and shape of the rudder, a set of hinges to attach the rudder to the boat, and some tools such as a saw, drill, and screws. You will also need some filler material such as wood putty or epoxy to finish and seal the rudder.

Before you can make your own rudder, you need to gather a few materials. Here is a list of the supplies you will need:

• Wooden boards • Screws • Nuts and bolts • Drill • Sandpaper • Epoxy resin • Paint

In terms of tools, you will need a saw, a drill, a hammer, and some sandpaper. You will also need a few clamps to help hold the pieces together while you are working on them.

Designing the Rudder

The first step in making a rudder for your sailboat is to design it. This is an important step as it will determine the size and shape of the rudder you will make. You should consider the size of your boat and the type of rudder you want to make. You will also need to determine the location of the rudder in relation to the keel. This will help you calculate the size of the rudder and the type of materials you will need.

After you have designed the rudder, you can now start to cut the wood. You will need to measure and mark the wood according to the design of the rudder. Make sure to use a saw or other cutting tool that is suited for the job. You should also use a drill to make holes for the nuts and bolts.

Shaping the Rudder

Once the wood has been cut to size, you can start to shape the rudder. This is an important step as it will determine how the rudder looks and how it performs. To do this, you can use a combination of sandpaper and a chisel to sculpt the wood into the desired shape. Make sure to sand the wood down until it is smooth and even.

Sh aping the rud der for a boat involves cutting and sand ing the rud der blank to the desired shape . This involves using a j igsaw , a s ander , and a file to achieve the desired shape . The rud der should be sand ed smooth and free from any sharp edges . It is important to ensure the surface of the rud der is smooth and free of any irregularities . Once the desired shape is achieved , it can be coated with a protective layer of paint or var n ish for added protection .

Attaching the Parts

Once the rudder is shaped, you can now attach the parts together. You will need to use screws, nuts, and bolts to secure the pieces of wood together. Make sure to use epoxy resin to help bond the pieces together.

Painting the Rudder

The last step in making a rudder for your sailboat is to paint it. This will help protect the wood from water damage and UV rays. You should use a marine-grade paint that is designed for boats. Make sure to apply a few coats to ensure the best protection.

Installing the Rudder

Once the rudder is painted, you can now install it on your boat. This is a relatively simple process that involves attaching the rudder to the stern of the boat. You will need to use bolts and nuts to secure the rudder in place.

Testing the Rudder

The last step in making a rudder for your sailboat is to test it. This is an important step as it will help you determine how the rudder will perform on the water. You should take the boat out on the water and try to steer it in different directions. This will help you make sure the rudder is working properly.

How to make a rudder for a small boat

To make a rud der for a small boat , you will need to first create a rud der template that is proportional to the size of the boat . This template should be cut out from a sheet of wood or plastic and should include the rud der blade , t iller arm , and mounting holes . Once the template is cut out , you will need to trace it onto the material that you will use to make the rud der .

After drilling the necessary holes , you will need to assemble the rud der blade and t iller arm . The rud der blade will need to be securely attached to the boat ’s trans om with bolts and screws . The t iller arm should also be attached to the boat ’s trans om using bolts and screws . Y ou will need to add a rud der g ud geon and pint le to the rud der blade and trans om , respectively . This will allow the rud der to be moved up and down and side to side .

Can I make a rudder from any type of wood, or does it have to be marine-grade plywood?

It’s best to stick with marine-grade plywood when crafting your rudder. Why? It’s specially designed to resist water, so it’ll last longer and perform better in the harsh marine environment. While you could technically use other types of wood, they may not stand up to the task and could leave you rudderless in the middle of the lake.

Is it necessary to paint the rudder after applying epoxy resin?

While the epoxy resin does provide a water-resistant seal, adding a layer of marine paint gives your rudder an extra layer of protection against UV damage and wear-and-tear.

Can I still make my own rudder?

Yes you can. While building a rudder does require some hands-on work, with the right tools, materials, and a bit of patience, it’s totally doable as a DIY project. Remember, every expert was once a beginner. Don’t be afraid to give it a try! If it seems overwhelming, there are plenty of tutorials and guides out there to help you navigate the process. Worst case scenario, you can always call in a pro.

Related posts:

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

My Cruiser Life Magazine

All About the Rudder on a Sailboat

The rudder on a sailboat is one of those important parts that often gets overlooked. It’s hidden underwater most of the time and usually performs as expected when we ask something of it.

But when was the last time you seriously considered your sailboat rudder? Do you have a plan if it fails? Here’s a look at various designs of sail rudder, along with the basics of how it works and why it’s there.

Table of Contents

How are sailboat rudders different than keels, how does the rudder work, wheel steering vs. tiller steering, full keel rudder sailboat, skeg-hung rudders, spade rudder, variations on designs, emergency outboard rudder options, looking to sail into the sunset grab the wheel, steer your sail boat rudder, and get out there, sail boat rudder faqs.

What Is a Boat Rudder?

The rudder is the underwater part of the boat that helps it turn and change direction. It’s mounted on the rear of the boat. When the wheel or tiller in the cockpit is turned, the rudder moves to one side or another. That, in turn, moves the boat’s bow left or right.

When it comes to sailing, rudders also offer a counterbalance to the underwater resistance caused by the keel. This enables the boat to sail in a straight line instead of just spinning around the keel.

Sailboat hull designs vary widely when you view them out of the water. But while the actual shape and sizes change, they all have two underwater features that enable them to sail–a rudder and a keel.

The rudder is mounted at the back of the boat and controls the boat’s heading or direction as indicated by the compass .

The keel is mounted around the center of the boat. Its job is to provide a counterbalance to the sails. In other words, as the wind presses on the sails, the weight of the ballast in the keel and the water pressure on the sides of the keel keeps the boat upright and stable.

When sailing, the keel makes a dynamic force as water moves over it. This force counters the leeway made by air pressure on the sails and enables the boat to sail windward instead of only blowing downwind like a leaf on the surface.

The rudder is a fundamental feature of all boats. Early sailing vessels used a simple steering oar to get the job done. Over the years, this morphed into the rudder we know today.

However, thinking about a rudder in terms of a steering oar is still useful in understanding its operation. All it is is an underwater panel that the helmsperson can control. You can maintain a course by trailing the oar behind the boat while sailing. You can also change the boat’s heading by moving it to one side or the other.

The rudders on modern sailboats are a little slicker than simple oars, of course. They are permanently mounted and designed for maximum effectiveness and efficiency.

But their operating principle is much the same. Rudders work by controlling the way water that flows over them. When they move to one side, the water’s flow rate increases on the side opposite the turn. This faster water makes less pressure and results in a lifting force. That pulls the stern in the direction opposite the turn, moving the bow into the turn.

Nearly all boats have a rudder that works exactly the same. From 1,000-foot-long oil tankers to tiny 8-foot sailing dinghies, a rudder is a rudder. The only boats that don’t need one are powered by oars or have an engine whose thrust serves the same purpose, as is the case with an outboard motor.

Operating the Rudder on a Sailboat

Rudders are operated in one of two ways–with a wheel or a tiller. The position where the rudder is operated is called the helm of a boat .

Ever wonder, “ What is the steering wheel called on a boat ?” Boat wheels come in all shapes and sizes, but they work a lot like the wheel in an automobile. Turn it one way, and the boat turns that way by turning the rudder.

A mechanically simpler method is the tiller. You’ll find tiller steering on small sailboats and dinghies. Some small outboard powerboats also have tiller steering. Instead of a wheel, the tiller is a long pole extending forward from the rudder shaft’s top. The helmsperson moves the tiller to the port or starboard, and the bow moves in the opposite direction. It sounds much more complicated on paper than it is in reality.

Even large sailboats will often be equipped with an emergency tiller. It can be attached quickly to the rudder shaft if any of the fancy linkages that make the wheel work should fail.

Various Sail Boat Rudder Designs

Now, let’s look at the various types of rudders you might see if you took a virtual walk around a boatyard. Since rudders are mostly underwater on the boat’s hull, it’s impossible to compare designs when boats are in the water.

Keep in mind that these rudders work the same way and achieve the same results. Designs may have their pluses and minuses, but from the point of view of the helmsperson, the differences are negligible. The overall controllability and stability of the boat are designed from many factors, and the type of rudder it has is only one of those.

You’ll notice that rudder design is closely tied to keel design. These two underwater features work together to give the boat the sailing characteristics the designer intended.

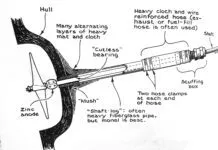

The classic, robust offshore sailboat is designed with a full keel that runs from stem to stern. With this sort of underwater profile, it only makes sense that the rudder would be attached to the trailing edge of that enormous keel. On inboard-powered sailboats, the propeller is usually mounted inside an opening called the aperture between the keel and rudder.

The advantages of this design are simplicity and robustness. The keel is integrated into the hull and protects the rudder’s entire length. Beyond reversing into an obstacle, anything the boat might strike would hit the keel first and would be highly unlikely to damage the rudder. Not only does the keel protect it, but it also provides a very strong connection point for it to be attached to.

Full keel boats are known for being slow, although there are modern derivatives of these designs that have no slow pokes. Their rudders are often large and effective. They may not be the most efficient design, but they are safe and full keels ride more comfortably offshore than fin-keeled boats.

Plenty of stout offshore designs sport full keel rudders. The Westsail 38s, Lord Nelsons, Cape Georges, Bristol/Falmouth Cutters, or Tayana 37s feature a full keel design.

A modified full keel, like one with a cutaway forefoot, also has a full keel-style rudder. These are more common on newer designs, like the Albergs, Bristols, Cape Dorys, Cabo Ricos, Island Packets, or the older Hallberg-Rassys.

A design progression was made from full keel boats to long-fin keelboats, and the rudder design changed with it. Designers used a skeg as the rudder became more isolated from the keel. The skeg is a fixed structure from which you can mount the rudder. This enables the rudder to look and function like a full keel rudder but is separated from the keel for better performance.

The skeg-hung rudder has a few of the same benefits as a full keel rudder. It is protected well and designed robustly. But, the cutaways in the keel provide a reduced wetted surface area and less drag underwater, resulting in improved sailing performance overall.

Larger boats featuring skeg-mounted rudders include the Valiant 40, Pacific Seacraft 34, 37, and 40, newer Hallberg-Rassys, Amels, or the Passport 40.

It’s worth noting that not all skegs protect the entire rudder. A partial skeg extends approximately half the rudder’s length, allowing designers to make a balanced rudder.

With higher-performance designs, keels have become smaller and thinner. Fin keel boats use more hydrodynamic forces instead of underwater area to counter the sail’s pressure. With the increased performance, skegs have gone the way of the dinosaurs. Nowadays, rudders are sleek, high aspect ratio spade designs that make very little drag. They can be combined with a number of different keel types, including fin, wing keels , swing keels, or bulb keels.

The common argument made against spade rudders is that they are connected to the boat by only the rudder shaft. As a result, an underwater collision can easily bend the shaft or render the rudder unusable. In addition, these rudders put a high load on the steering components, like the bearings, which are also more prone to failure than skeg or full keel designs. For these reasons, long-distance cruisers have traditionally chosen more robust designs for the best bluewater cruising sailboats .

But, on the other hand, spade rudders are very efficient. They turn the boat quickly and easily while contributing little to drag underwater.

Spade rudders are common now on any boat known for performance. All racing boats have a spade rudder, like most production boats used for club racing. Pick any modern fin keel boat from Beneteau, Jeanneau, Catalina, or Hunter, and you will find a spade rudder. Spade rudders are common on all modern cruising catamarans, from the Geminis to the Lagoons, Leopards, and Fountaine Pajots favored by cruisers and charter companies.

Here are two alternative designs you might see out on the water.

Transom-Hung or Outboard Rudders

An outboard rudder is hung off the boat’s transom and visible while the boat is in the water. Most often, this design is controlled by a tiller. They are common on small sailing dingies, where the rudder and tiller are removable for storage and transport. The rudder is mounted with a set of hardware called the pintle and gudgeon.

Most outboard rudders are found on small daysailers and dinghies. There are a few classic big-boat designs that feature a transom-hung rudder, however. For example, the Westsail 38, Alajuela, Bristol/Falmouth Cutters, Cape George 36, and some smaller Pacific Seacrafts (Dana, Flicka) have outboard rudders.

Twin Sailing Rudder Designs

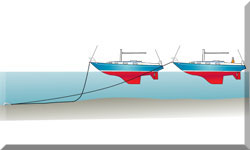

A modern twist that is becoming more common on spade rudder boats is the twin sailboat rudder. Twin rudders feature two separate spade rudders mounted in a vee-shaped arrangement. So instead of having one rudder pointed down, each rudder is mounted at an angle.

Like many things that trickle down to cruising boats, the twin rudder came from high-performance racing boats. By mounting the rudders at an angle, they are more directly aligned in the water’s flow when the boat is healed over for sailing. Plus, two rudders provide some redundancy should one have a problem. The twin rudder design is favored by designers looking to make wide transom boats.

There are other, less obvious benefits of twin rudders as well. These designs are easier to control when maneuvering in reverse. They are also used on boats that can be “dried out” or left standing on their keel at low tide. These boats typically combine the twin rudders with a swing keel, like Southerly or Sirius Yachts do. Finally, twin rudders provide much better control on fast-sailing hulls when surfing downwind.

Unbalanced vs. Balanced Rudders

Rudders can be designed to be unbalanced or balanced. The difference is all in how they feel at the helm. The rudder on a bigger boat can experience a tremendous amount of force. That makes turning the wheel or tiller a big job and puts a lot of strain on the helmsperson and all of the steering components.

A balanced rudder is designed to minimize these effects and make turning easier. To accomplish this, the rudder post is mounted slightly aft of the rudder’s forward edge. As a result, when it turns, a portion of the leading edge of the rudder protrudes on the opposite side of the centerline. Water pressure on that side then helps move the rudder.

Balanced rudders are most common in spade or semi-skeg rudders.

Sail Rudder Failures

Obviously, the rudder is a pretty important part of a sailboat. Without it, the boat cannot counter the forces put into the sails and cannot steer in a straight line. It also cannot control its direction, even under power.

A rudder failure of any kind is a serious emergency at sea. Should the rudder be lost–post and all–there’s a real possibility of sinking. But assuming the leak can be stopped, coming up with a makeshift rudder is the only way you’ll be able to continue to a safe port.

Rudder preventative maintenance is some of the most important maintenance an owner can do. This includes basic things that can be done regularly, like checking for frayed wires or loose bolts in the steering linkage system. It also requires occasionally hauling the boat out of the water to inspect the rudder bearings and fiberglass structure.

Many serious offshore cruisers install systems that can work as an emergency rudder in extreme circumstances. For example, the Hydrovane wind vane system can be used as an emergency rudder. Many other wind vane systems have similar abilities. This is one reason why these systems are so popular with long-distance cruisers.

There are also many ways to jury rig a rudder. Sea stories abound with makeshift rudders from cabinet doors or chopped-up sails. Sail Magazine featured a few great ideas for rigging emergency rudders .

Understanding your sail rudder and its limitations is important in planning for serious cruising. Every experienced sailor will tell you the trick to having a good passage is anticipating problems you might have before you have them. That way, you can be prepared, take preventative measures, and hopefully never deal with those issues on the water.

What is the rudder on a sailboat?

The rudder is an underwater component that both helps the sailboat steer in a straight line when sailing and turn left or right when needed.

What is the difference between a rudder and a keel?

The rudder and the keel are parts of a sailboat mounted underwater on the hull. The rudder is used to turn the boat left or right, while the keel is fixed in place and counters the effects of the wind on the sails.

What is a rudder used for on a boat?

The rudder is the part of the boat that turns it left or right

Matt has been boating around Florida for over 25 years in everything from small powerboats to large cruising catamarans. He currently lives aboard a 38-foot Cabo Rico sailboat with his wife Lucy and adventure dog Chelsea. Together, they cruise between winters in The Bahamas and summers in the Chesapeake Bay.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Understanding boat rudders: Navigating the key component for smooth sailing

Navigating a boat requires a complex interplay of various components, and one of the most crucial elements is the rudder. In this comprehensive guide, we will delve into the world of boat rudders, exploring their functionality, importance, and role in steering a ship to smooth sailing.

What are boat rudders?

Boat rudders are an essential component of the vessel's steering system. They are hydrofoil-like structures located at the stern (rear) of the boat, underwater. The primary function of the rudder is to control the direction of the boat by redirecting the flow of water as the boat moves forward.

The role of boat rudders in steering

Boat rudders play a vital role in steering a ship. When the helmsman turns the wheel or tiller, the rudder changes its angle, redirecting the water flow on one side of the boat, creating more resistance on that side, and causing the boat to turn in the opposite direction.

Types of boat rudders

Spade rudders: Spade rudders are simple and streamlined rudders attached directly to the hull. They are commonly found in modern sailboats and provide excellent maneuverability and responsiveness.

Skeg rudders: Skeg rudders are partially submerged and supported by a skeg, a vertical extension of the hull. These rudders offer increased protection and are often used in larger motorboats and trawlers.

Balanced rudders: Balanced rudders have a portion of the rudder forward of the pivot point, which balances the force applied by the helmsman. This design reduces the effort required to steer the boat.

Barn door rudders: Barn door rudders are large, flat, and wide rudders resembling barn doors. They are commonly seen in traditional fishing vessels and provide excellent control in rough seas.

Spade hung rudders: Spade hung rudders are free-floating rudders attached to the boat only at the top, allowing them to swing freely. They are commonly used in high-performance sailing yachts.

Read our top notch articles on topics such as sailing, sailing tips and destinations in our Magazine .

Components and mechanics of boat rudders

A typical boat rudder consists of several key components:

Rudder blade: The rudder blade is the flat, vertical surface responsible for redirecting the water flow. It is the most critical part of the rudder and comes in various shapes and sizes.

Rudder stock: The rudder stock is a sturdy vertical shaft that connects the rudder blade to the steering mechanism. It provides the necessary support and stability for the rudder.

Tiller or wheel: The tiller or wheel is the steering control operated by the helmsman. When turned, it causes the rudder to change its angle and steer the boat.

Rudder bearings: Rudder bearings are the mechanisms that allow the rudder to pivot smoothly on the rudder stock. Properly lubricated and maintained bearings ensure easy steering.

Steering linkage: The steering linkage consists of rods or cables connecting the tiller or wheel to the rudder stock. It transmits the helmsman's steering inputs to the rudder.

Steering a ship: The interaction between rudder and helm

The process of steering a ship involves a coordinated effort between the rudder and the helm. When the helmsman turns the wheel or tiller, the rudder angle changes, causing a difference in water flow on either side of the boat. This creates a force imbalance, turning the boat in the desired direction.

The effectiveness of the steering system depends on various factors, such as the rudder's size, shape, and angle, the vessel's speed, and the water conditions. Proper coordination between the helmsman and the rudder is essential for precise maneuvering.

Maintaining and repairing boat rudders

Regular maintenance is crucial to ensure the optimal performance and longevity of boat rudders. Here are some maintenance tips:

Inspect for damage: Regularly inspect the rudder blade, stock, and bearings for any signs of wear, damage, or corrosion.

Lubrication: Ensure the rudder bearings are well-lubricated to prevent friction and allow smooth movement.

Antifouling: Apply antifouling paint to the rudder to prevent marine growth, which can negatively impact performance.

Check steering linkage: Inspect and adjust the steering linkage regularly to maintain precise control.

Address issues promptly: If any problems or abnormalities are detected, address them promptly to prevent further damage.

Rudder design innovations

Advancements in technology have led to innovative rudder designs aimed at improving performance and efficiency. Some notable innovations include:

Hydrodynamic profiles: Rudder blades are now designed with advanced hydrodynamic profiles to reduce drag and enhance maneuverability.

Rudder fins: Some rudders are equipped with additional fins or foils to improve stability and minimize yawing motion.

Retractable rudders: Certain sailboats feature retractable rudders, which can be raised when sailing in shallow waters, reducing the risk of grounding.

Steer-by-wire systems: Modern vessels are adopting steer-by-wire systems, replacing traditional mechanical linkages with electronic controls for smoother steering.

The influence of rudder size and shape on turning radius

The size and shape of the rudder directly impact the vessel's turning radius. Larger rudders with greater surface area provide more steering force and can turn the boat more quickly. However, larger rudders also create more drag, which can affect overall speed and fuel efficiency. The optimal rudder size depends on the boat's size, weight, and intended use.

Rudder efficiency and hydrodynamics

The hydrodynamics of the rudder significantly affect its efficiency. Smooth and streamlined rudder designs minimize drag and turbulence, resulting in improved performance and fuel economy. Advanced hydrodynamic analysis and simulation tools help optimize rudder shapes for various vessels and operating conditions.

Common rudder issues and troubleshooting

Like any mechanical component, boat rudders can experience issues over time. Some common problems and troubleshooting tips include:

Stiff steering: If the steering feels stiff or unresponsive, check for obstructions in the rudder bearings or linkage.

Vibrations: Vibrations during steering may indicate misaligned rudder blades or bent rudder stocks.

Leaking bearings: Leaking rudder bearings require immediate attention to prevent water ingress and corrosion.

Excessive play: Excessive play in the rudder could be due to worn steering linkage or loose connections.

Reduced maneuverability: Reduced maneuverability may result from a fouled or damaged rudder blade.

Rudder steering systems

Various steering systems are employed in conjunction with rudders, each offering unique advantages:

Tiller steering: Common in smaller boats, tiller steering directly connects the tiller to the rudder stock, providing direct and responsive control.

Wheel steering: Larger boats often use wheel steering, which utilizes a mechanical or hydraulic system to transfer steering inputs to the rudder.

Hydraulic steering: Hydraulic steering systems offer smooth and effortless steering, ideal for larger vessels.

Electric steering: Electric steering systems, also known as electro-hydraulic steering or electronic power steering (EPS), utilize electric motors to assist in steering the boat. These systems work in conjunction with hydraulic components, making steering more effortless and responsive for the boat operator.

So what are you waiting for? Take a look at our range of charter boats and head to some of our favourite sailing destinations .

FAQs about rudders

The Types of Sailboat Rudders

- Snowboarding

- Scuba Diving & Snorkeling

Full Keel Rudder

On a sailboat , as the rudder is moved to one side by means of the tiller or steering wheel, the force of the water striking one edge of the rudder turns the stern in the other direction to turn the boat. Different types of rudders have different advantages and disadvantages. The type of rudder is often related to the boat’s type of keel.

Rudder on Full-Keel Sailboat

As shown in this photo, the rudder of a full-keel boat is usually hinged to the aft edge of the keel, making a continuous surface. The engine’s propeller is usually positioned in an aperture between the keel and rudder.

Advantages of Full Keel Rudder