Fleming 58/60

Specification, virtual tour.

- Download Brochure

- Download Full Spec

- Make Enquiry

Exceptional Yachting

After extensive research and input from existing Fleming owners, we identified the need for a boat to bridge the gap between the Fleming 55 and the 65. While retaining the Fleming classic lines, the 58 is an entirely new boat designed from the keel up. The naval architects selected to assist the in-house Fleming design team were Norman Wright and Sons in Brisbane, Australia who, with their special expertise in hull design and tank testing, have been designing semi-displacement passagemakers for more than 100 years.

The latest 3D modeling and CAD software were employed during the design process and a 1/12 scale model was built and tank tested at the Australian Maritime College in Tasmania. Several load conditions were simulated at varying speeds to determine resistance, trim and other performance parameters.

The Fleming 58 is also available as a Fleming 60, which extends the transom aft allowing for some molded seating with a crew cabin under.

Boat Enquiry

- GDOR Tick this box if you are happy to receive marketing communications - The personal data you supply will not be passed on to third parties for commercial purposes. Data collected by us is held in accordance with the UK Data Protection Act. All reasonable precautions are taken to prevent unauthorised access to this information.

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- 1 / 27

- LOA 62' 9 (19.1m)

- LOA (w/swim and anchor platforms) 65' 9 (19.9 m)

- LWL 56' 8 (17.3m)

- Beam 17' 6 (5.33m)

- Draft 5' (1.52m)

- Air Draft (to top of arch) 17' (5.18m)

- Displacement 88,000 lbs. (39,916 kg)

- Fuel 1,450 US gal (5,488 litres)

- Water 320 US gal (1,211 litres)

- Hull 58-019

- Hull 58-009

- Hull 58-001

- Hull 58-028

Newsletter sign-up

Sign-up to receive updates and promotions.

- Email address *

You can amend or withdraw consent at any time by emailing us. Further details regarding how we process your personal data can be found in our Privacy Policy .

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

- Sirena Yachts

- Boats for sale

- Service & Maintenance

- Upcoming Boatshows

- The Company

- All products

Fleming 58 Contact us

On the 25th anniversary of the founding of the company, Fleming Yachts were proud to announce the introduction of the all-new Fleming 58.

After extensive research and input from existing Fleming owners, we identified the need for a boat to bridge the gap between the Fleming 55 and the 65. While retaining the Fleming classic lines, the 58 is an entirely new boat designed from the keel up. The naval architects selected to assist the in-house Fleming design team were Norman Wright and Sons in Brisbane, Australia who, with their special expertise in hull design and tank testing, have been designing semi-displacement passagemakers for more than 100 years.

The latest 3D modeling and CAD software were employed during the design process and a 1/12 scale model was built and tank tested at the Australian Maritime College in Tasmania. Several load conditions were simulated at varying speeds to determine resistance, trim and other performance parameters.

For more information and VR-Tour

Standard Specification

| LOA: | 65' 9' (19.9 m) |

| LWL: | 56' 8' (17.3 m) |

| Beam: | 17' 6' (5.33 m) |

| Draft: | 5' (1.52 m) |

| Air Draft: | 17' (5.18 m) |

| Displacement Light: | 88,000 lbs (40,000 kg) |

| Displacement Full: | 105,600 lbs (48,000 kg) |

| Fuel: | 1,450 US gal (5,488 l) |

| Water: | 320 US gal (1,211 l) |

For more information and VR-Tour

Welcome to Marstrand Yachts

Social Media

Marstrand Yachts - Fleming Marstrand Yachts - Cormate Marstrand Yachts - Sirena Yachts Instagram

Fleming Sirena Yachts

The Company Contact

Privacy policy Cookies

Marstrand Yachts Hamngatan 25A SE-442 67 Marstrand Sweden

Marstrand Yachts Skogsövägen 22 SE-133 33 Stockholm Sweden

Marstrand Yachts Holunderweg 30 31535 Neustadt am Rbge Germany

Come and see us at the indoor fair "Allt för sjön" in Stockholm, 7-10 & 14-17 March. Right now! Cormate x 2 at fair price.

Sirena 48 at Boot Düsseldorf 20-28 January. Book your appointment for private viewing now!

Unique opportunity! Fleming Yachts 55 x 2 for sale

Unique prices on cormate su23 and t28 demo boats valid until september 2023, world premiere sirena 48.

Discover Sirena 48 Brand new in the Sirena Yacht Family

More>>

Weekend Boat Show

Fleming Yachts at Aker Brygge, Oslo 31 August - 3 September

Sirena Yacht at Gustavsberg, Stockholm 1-3 September

Read more here >>

Curious about Fleming Yacht and Sirena Yacht Book your private tour during Eriksberg's boat fair April 14-16

Make your reservation>>

Come for a sea trial with our Cormate boats at Waterfront Day's, Nacka Strand, April 27-30

Sign up here

We welcome the new member of the Sirena family - SIRENA 78

Upcoming boat shows >> Come and visit us at Cannes Yachting Festival September 10-15

Sign up for upcoming boatshows >>

Keep up to date

Sign up for our newsletter so you do not miss any news.

| Necessary Cookies | Off | |

| Performance Cookies | Off | |

| Marketing Cookies | Off | |

2024 Fleming 58

- Phone (optional)

- RE: 2024 Fleming 58

- [bws_google_captcha]

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Asking: $ 0

Description.

New Fleming 58 Build – Contact us or visit our website for full details on new Fleming Yachts as well as view our list of Previously Cruised Flemings for sale.

- SPECIFICATION

| LOA-Hull | 58 |

| LOA-Total | 65.42 |

| BEAM | 17 |

| DRAFT | 5 |

| ENGINES | MAN i6 @ 800 hp |

| EFFICIENT CRUISE SPEED | 17 Kt |

| HIGH CRUISE SPEED | 21 Kt |

| FUEL CAPACITY | 1,450 gal |

| WATER CAPACITY | 320 gal |

| BLACKWATER CAPACITY | 165 gal |

The Company offers the details of this vessel in good faith but cannot guarantee or warrant the accuracy of this information nor warrant the condition of the vessel. A buyer should instruct his agents, or his surveyors, to investigate such details as the buyer desires validated. This vessel is offered subject to prior sale, price change, or withdrawal without notice.

Sign Up for Our Email Updates

Inquire About This Yacht

On the 25th anniversary of the founding of the company, Fleming Yachts were proud to announce the introduction of the all-new Fleming 58.

After extensive research and input from existing Fleming owners, we identified the need for a boat to bridge the gap between the Fleming 55 and the 65. While retaining the Fleming classic lines, the 58 is an entirely new boat designed from the keel up. The naval architects selected to assist the in-house Fleming design team were Norman Wright and Sons in Brisbane, Australia who, with their special expertise in hull design and tank testing, have been designing semi-displacement passagemakers for more than 100 years.

The latest 3D modeling and CAD software were employed during the design process and a 1/12 scale model was built and tank tested at the Australian Maritime College in Tasmania. Several load conditions were simulated at varying speeds to determine resistance, trim and other performance parameters.

Standard Specifications

65' 9 (19.9 m)

56' 8 (17.3 m)

17' 6 (5.33 m)

5' (1.52 m)

17' (5.18 m)

Displacement Light:

88,000 lbs (40,000 kg)

Displacement Full:

105,600 lbs (48,000 kg)

1,450 US gal (5,488 l)

320 US gal (1,211 l)

View Full Specs

Fleming 58 Specifications

View Brochure

Hull 58-019

Hull 58-009

Hull 58-001

Hull 58-028

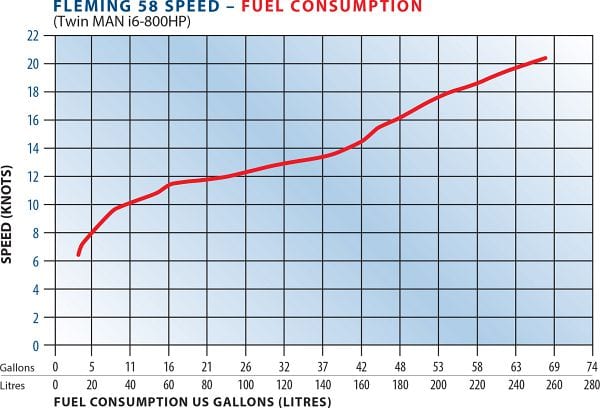

Performance Curves

Complete Overview

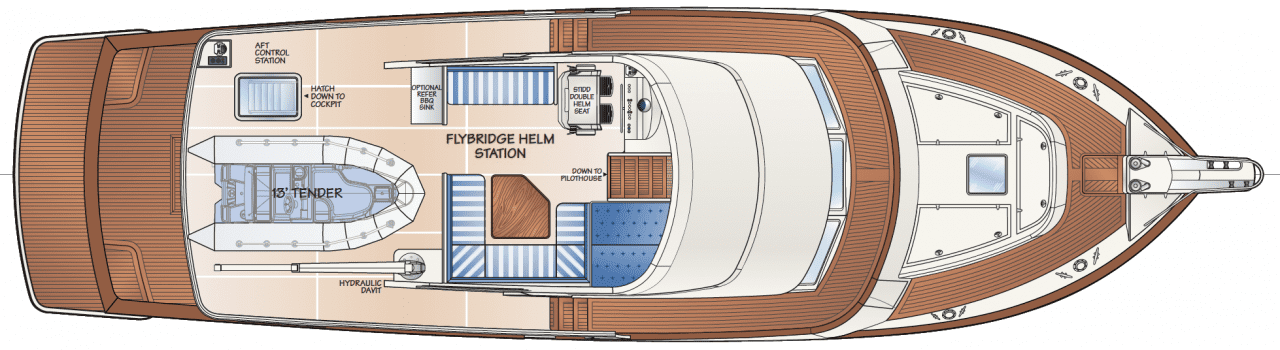

The Flybridge — Familiar but with More Function

More Amenities

The larger flybridge can accommodate a top-loading freezer, a refrigerator, BBQ and a 13ft (3.9m) Tender. The double Stidd helm seat provides comfortable, adjustable seating.

A fully hydraulic 1,000 lb. Steelhead davit, with power rotation and telescopic boom makes launching and retrieving the tender an easy and safe task, even single handed.

Refined Salon and True Pilothouse with Twin Helm Seats

Among the Innovations being offered on this and all Fleming Yachts is "Burrwood" a composite substitute for teak rail capping. This fiberglass material, manufactured and installed at the yard, replicates the exact appearance of varnished teak without the need for continual varnishing.

Anchor Platform accommodates dual Maxwell RC12 vertical windlasses to handle the 100 lb (45 Kg) stainless steel Ultra anchor and 7/16" Grade-60 stainless steel chain.

Easy Boarding is retained through the wide side deck boarding gates. Port and starboard gates through the Portuguese Bridge lead to the foredeck.

Large Access Hatch into the engine room is just aft of the salon doors.

More Space - The wider pilothouse, has space for twin Stidd helm seats.

Traditional Layout - The "Flow" of the Fleming

The 58 employs much of the same technology used in the Fleming 65 including the Fleming First Mater (FFM) ship monitoring system with two 15" color touchscreens, Hypro fly-by-wire precision power steering, and Seatorque's enclosed shaft system.

Placement of air-conditioning compressors and watermaker are all located in the expanded engine room - leaving the lazarette clear for storage.

Significantly more headroom in the engine room and more space forward and outboard of the engines. The standard engines on the Fleming 58 are the MAN i6-800.

Pilothouse with Enough Space for Twin Helm Seats and a Day-Head

The Fleming 58 provides an ideal intermediate size between the existing F55 and F65, and is easily operated by a couple.

The Cockpit is capacious - larger than the Fleming 55 by 25 sq. ft. (2.3 sq. meters). The built-in cabinets either side of the salon aft doors provide for a variety of options including a fridge/freezer, sink, and an aft control station

Two inward opening gates on either side of the Fleming 58 make boarding easy and safe.

A Built-in settee or matching barrel chairs provide additional seating in the salon, the extra beam of the Fleming 58 is most noticeable in the Salon & Pilothouse.

The Convenience of a Day-Head.

Lockers on either side of the anchor platform and storage bins in the cabin trunk provide stowage for lines and fenders.

The New Full Beam Master Cabin

New Layout - The Fleming 58 offers a variety of accommodation layouts, including a full beam, master cabin with access from the pilothouse.

Engine Room

Standard Power is a pair of MAN i6-800 engines. Standard equipment is the very efficient Seatorque shaft system which transfers thrust from the propellers directly to the hull structure and eliminates the need for cutless bearings and stuffing boxes.

The Tank Tested semi-displacement hull is a modern design based on the well proven Fleming 55. A fine entry and generous flare on the bow makes for an efficient, comfortable, and safe ride.

Spacious walk-in engine room - with access to all equipment and systems.

Proud Craftsmanship and a Passion for Yacht Building.

The Fleming 58 is, of course, built at the renowned Tung Hwa yard in Southern Taiwan, where every Fleming ever built has been constructed, starting with Fleming 50 hull 001 in 1985. Tung Hwa build exclusively for Fleming and many craftsmen from the early days are still with us. They are very proud of their work and their experience, passion and skill are passed down from one generation to the next.

Specifications

- LOA (Hull): 62' 9" (19.1m)

- LOA (w/ swim and anchor platforms): 65' 9" (19.9m)

- LWL: 56' 8" (17.3m)

- Beam: 17' 6" (5.33m)

- Draft: 5' (1.52m)

- Air draft (to top of radar arch): 17' (5.18m)

- Minimum Operating Condition: 88,000 Lbs. (39,916kg)

- Loaded Condition: 105,600 Lbs. (47,899kg)

- Main Engines: Twin MAN i6-800 (800 HP @ 2300 RPM)

- Transmission: Twin Disc MGX-5126A or ZF 360A with electric shift and troll valves

- Reduction Ratio: 2.50:1

- Engine Controls: Glendinning EEC3 (with back-up system)

- Generator: 17Kw, 60Hz Onan eQD (European model 13.5Kw, 50Hz)

- Stabilizers: ABT TRAC 7.5 Sq. Ft fins with winglets 250 model actuators

- Fuel Tanks: 1,450 USG (5,488 Liters) in two fibreglass tanks

- Water Tanks: 320 USG (1,211 Liters) in two polyethylene tanks

- Black Water Tank: 165 USG (625 Liters)

Download Specs Document

Our Inventory

- our inventory

58 Pilothouse In Stock

Call for price.

| Location | Sidney, BC |

|---|---|

| Condition | New |

| Category | Motor Yachts |

| Overall Length | 58 Feet |

| Year | 2019 |

| Hull Material | Fiberglass |

| Hull Beam | 17.5 Feet |

| Fuel Capacity | 1450 gal |

| Engine Power | 1600.0 HP |

| Engine 1 Make & Model | MAN |

| Engine 1 Type | |

| Engine 1 Fuel | |

| Engine 2 Make & Model | MAN |

| Engine 2 Type | |

| Engine 2 Fuel | diesel |

Factory Options Included

- Side power Bow and Stern Thrusters, with proportional speed control

- Fuel transfer and polishing system

- Second Generator - Onan 17KW

- Auto anchor chain counter, wireless, two station

- 50' long 220VAC, 50amp Shore power cord (custom)

- Additional 110V-30A aft shore power connection

- House battery bank to be 900A/H

- Install owner supplied transducers (3)

- CCTV System 4 pan/tilt/zoom camera (E/R, Cockpit, F/B) Boning System control

- Docking Cameras (fwd/aft) installed port / stbd connected to Boning System

- Install "T" drain fittings for winterizing exterior water outlets

- Fin cutters forward of stabilizer fins

- Webasto cooling/heating system in lieu of Cruisair and prep for diesel heat

- Teak on swim step (non skid is standard)

- Illuminated name boards, with name in stainless steel letters

- FRP "Burrwood" cap rails in lieu of teak

- "Smart" spray rails

- Teak on forward deck ( Beige non-skid is standard)

- Teak on anchor platform lids ( white non-skid is standard)

- Anchor platform stainless steel dirty water catchment fence

- Anchor chain wash system, on/off switches at P/H & F/B & foot switch on foredeck

- Cockpit console, starboard side with lid, engine & thruster controls & start & stop buttons

- Port side cockpit cabinet with storage, wet locker and molded stairs to flybridge

- 50 amp Cablemaster installed starboard side

- Warping winch starboard side only

- Two removable stainless steel rails on swim step

- Fold-up cleats on swim step

- Opening lid on port cockpit seat locker

- Factory Options Included - Fleming 58- Hull #025

- Aft boatdeck control station with engine and thruster controls

- Teak on flybridge

- Low level LED courtesy lighting under seating around flybridge

- Cushion forward of starboard settee on fly bridge

- 2 x 10lb propane cylinders with regulators and plumbing under flybridge port side seat

- Isotherm refrigerator in cabinet aft of port fly bridge seating

- Hardtop with opening skylights and LED lighting

- Two aft facing flood lights at aft end of boatdeck

- Section of flybridge rail removable at liferaft location portside

- BBQ plumbing in cabinet on aft deck

- High gloss teak table top

- Layout A - 3 cabins, 2 heads, central passageway and pilothouse day head

- 2 x Barrel chair for salon, Ultra-leather - Brisa Distressed Chamois

- Corian"Sandlewood" finish in guest head, countertop and shower stall

- Corian "Sandalwood" finish in master head, countertop and shower stall

- High gloss on leerails

Master cabin

- Teak on upper bulkheads (in lieu of ultraleather)

- Lift up vanity with mirror and lights on port side hull locker

- Upper berth (outboard sliding type)

- Starboard cabin

- AC outlet inside pilothouse console, behind airconditioning return grill

- Install Ultra-leather upholstery on pilothouse seating - Brisa Distressed Chamois

- Install circuit breaker and two 24VDC power cables to helm seat pedestal

- Custom finish on pilothouse table - Compass Rose inlay

- Stidd seat to have port and starboard armboxes for remote joysticks

- High gloss finish on pilothouse table

- Upgrade microwave to stainless steel finish

- Miele slim-line 18" dishwasher with teak front panel

- Granite on galley counter top - Galassia Gold

- Bullnose finish on galley granite

- Custom L-shaped bar aft of salon settee, with overhead lockers, glass doors

- U-Line wine cooler in cabinet aft of galley fridge

- Bennett TV lift in aft starboard corner of salon

- Install Ultra-leather upholstery on salon settee Brisa Distressed Chamois with double stitching

- High Gloss finish on salon table

- Overhead teak handrail

Local Commissioning Completed

Electronics

- 2 - Hatteland 24" Touch Screen Monitors

- 2 - Hatteland 15" Touch Screen Monitors

- 1 - Hatteland 17" Touch Screen Monitor

- Furuno DRS12AX Radar Base and XN13A/6 Open Array Antenna

- Furuno FA50 AIS Class B Transceiver

- Furuno Hub 101 Network Hub

- Furuno NAVPILOT 711C Auto Pilot

- Furuno FAP 7011A Remote Autopilot

- 5 - Furuno FI-70 Displays Color Data Organizer

- 3 - Furuno TZTBB Black Box System

- Furuno GP330B GPS

- Furuno DST800L Retractable Smart Sensor Thru Hull

- Furuno 525SSTID-MSD7 Bronze Transducer

- Mareton WSO100 Weather System

- Furuno SC30 Satellite Compass

- Furuno MCU-004 Remote Controllers

- 2 - Icom M506 VHF Radio

- Icom HM195 Command Mic

- Wave WFI

- mounting brackets, microphones, antennas, cables, hardware, etc.

- Sea Recovery Aqua Matic A14C1800-2 Watermaker

- Remote Colour Display in Pilothouse

- Victron Blue Power 3000kw Inverter

- Golight 30204 Search Light

- 2 x Blank Domes ( for later installation of antenna & satellite receiver)

- Custom Aluminium / Folding Yacht style mast

Safety Equipment

- Life Line & Throw Bag

- First Aid Kit & Safety Kit

- Dock Lines & Fenders

- Life Jackets & Life Rings

- Fire Extinguishers

Flybridge

- Full Canvas Enclosure

More Information

Please contact us directly for more information

The Company offers the details of this vessel in good faith but cannot guarantee or warrant the accuracy of this information nor warrant the condition of the vessel. A buyer should instruct his agents, or his surveyors, to investigate such details as the buyer desires validated. This vessel is offered subject to prior sale, price change, or withdrawal without notice.

Would you like more information?

Call us at Vancouver: 604-687-8943 or Sidney: 250-656-8909. Don't feel like talking? You can contact us using the form below.

Disclaimer: The Company offers the details of this vessel in good faith but cannot guarantee or warrant the accuracy of this information nor warrant the condition of the vessel. A buyer should instruct his agents, or his surveyors, to investigatge such details as the buyer desires validated. Price, if shown, may not include applicable state or government fees, taxes, destination charges, preparation charges, or finance charges (if applicable). Final actual sales price may vary depending on options or accessories selected. This vessel is offered subject to prior sale, price change, manufacturer revision, or withdrawal without notice.

Handcrafted by T2H Advertising | Privacy Policy

By continuing to use this website, you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our privacy policy.

Western Canada's Authorized Beneteau Dealer

Set sail with a new beneteau.

See the latest from Beneteau

We have high visibility docks

When it's easy to see, it's easier to sell..

List with us

Our Reputation Speaks for Itself

Integrity with Results

Our Services

We at Grand Yachts Inc. are passionate about boating, we enjoy building relationships with our clients and we strive to meet their expectations.

Our history runs deep and wide: We have specialized in fine yachts since 1976 as a new boat dealership and a yacht brokerage with two locations in British Columbia — Vancouver and Sidney, on Vancouver Island. The products that we have chosen to represent are high quality brands which suit the waterways and oceans of the Pacific Northwest. As the world changes we adapt.

Featured Inventory

37 Flybridge

LENGTH: 37 ft

PRICE: $429,000 CAD

View Details

55 Pilothouse

LENGTH: 55 ft

PRICE: Call for price

Boathouse 82'L x 30'W x 33'H

LENGTH: 82 ft

PRICE: $275,000 CAD

LENGTH: 60 ft

PRICE: $895,000 CAD

Tiara Yachts

3500 express.

LENGTH: 41 ft

PRICE: $199,000 CAD

Skylounge 630

LENGTH: 64 ft

PRICE: $775,000 CAD

58 Pilothouse

LENGTH: 58 ft

LENGTH: 46 ft

PRICE: $149,000 CAD

Two Great Locations in B.C.

See our current inventory of sailboats and motor yachts.

Testimonials

Christopher friesen, beth and dave o'connor - bellingham, w.a. | beneteau 36.7 owners.

We recently purchased our Beneteau 36.7 with the assistance of Brad Marchant. Due to the COVID-19 situation, we were unable to view the boat prior to purchasing it.

Ralf and Helga Schmidtke | Fleming 65 Owners

Having decided after 30 years of sailing to change to power, the wide choice of brands made the selection task a daunting one. We wanted the most reliable, comfortable, safest, practical and best thought out boat that we could find. Attention to detail and quality was paramount, as was after purchase servicing. She also had to be an attractive boat that we could be proud of. After several months of extensive research, one name easily made it to the top.

Joel Nauss | 75’ President Yacht Owners

Craig and stacey | beneteau oceanis 31.1 owners.

Stacey and I both want to extend our gratitude for your help in acquiring "Margie." She is exactly what we were looking for, and the entire process was as seamless as you had described it would be. She did well on our trip from Anacortes to Kirkland.

By continuing to use this website, you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our privacy policy.

proposing a research study

Have a language expert improve your writing.

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on October 12, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on November 21, 2023.

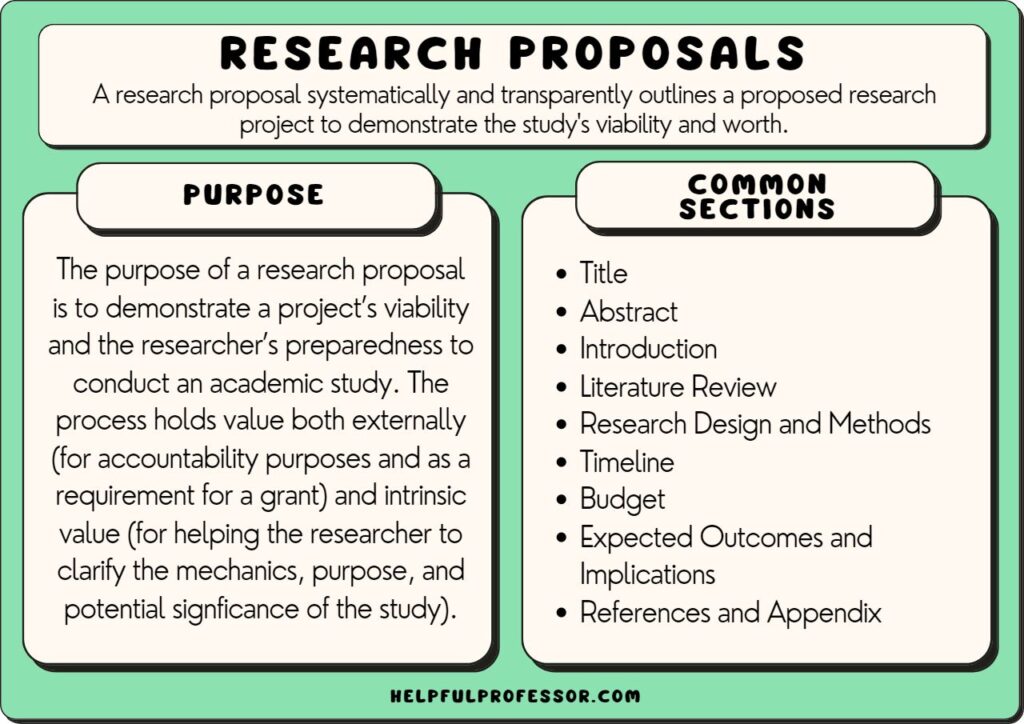

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

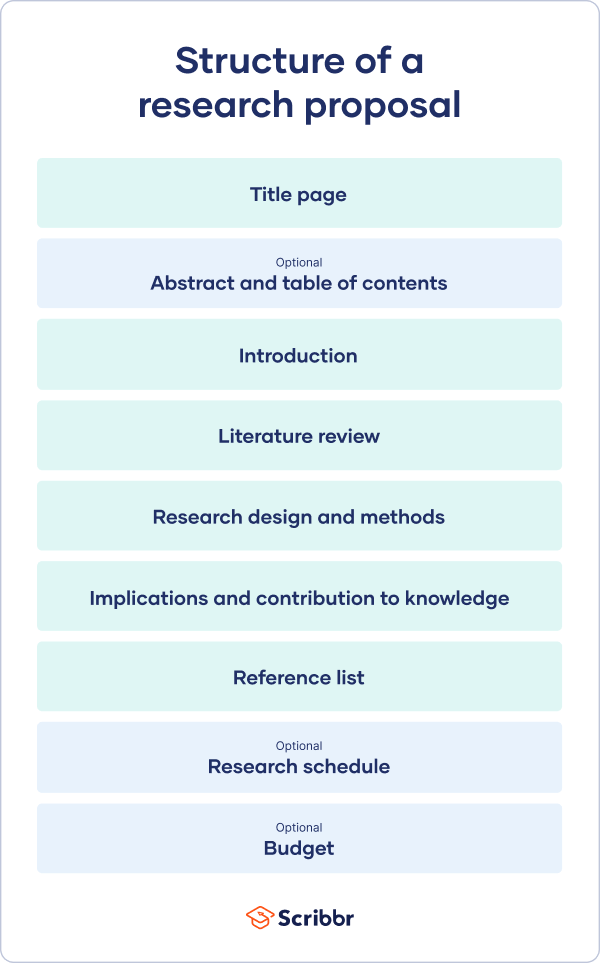

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organized and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

- Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research proposals.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

| Show your reader why your project is interesting, original, and important. | |

| Demonstrate your comfort and familiarity with your field. Show that you understand the current state of research on your topic. | |

| Make a case for your . Demonstrate that you have carefully thought about the data, tools, and procedures necessary to conduct your research. | |

| Confirm that your project is feasible within the timeline of your program or funding deadline. |

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

Download our research proposal template

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: “A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management”

- Example research proposal #2: “Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use”

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesize prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

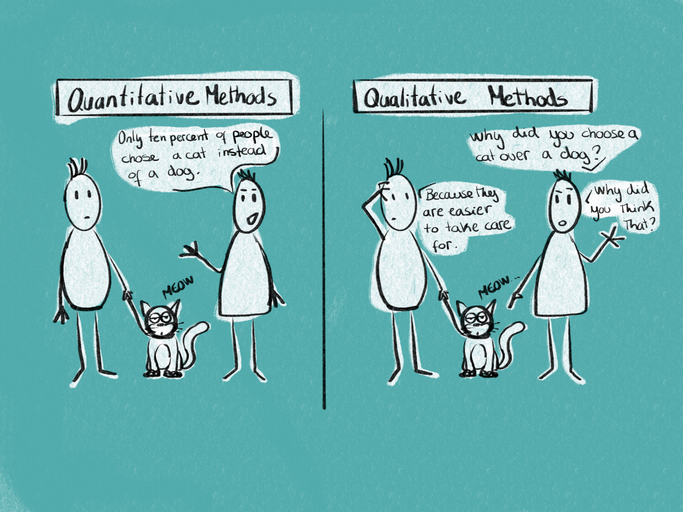

| ? or ? , , or research design? | |

| , )? ? | |

| , , , )? | |

| ? |

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

| Research phase | Objectives | Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Background research and literature review | 20th January | |

| 2. Research design planning | and data analysis methods | 13th February |

| 3. Data collection and preparation | with selected participants and code interviews | 24th March |

| 4. Data analysis | of interview transcripts | 22nd April |

| 5. Writing | 17th June | |

| 6. Revision | final work | 28th July |

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

The best way to remember the difference between a research plan and a research proposal is that they have fundamentally different audiences. A research plan helps you, the researcher, organize your thoughts. On the other hand, a dissertation proposal or research proposal aims to convince others (e.g., a supervisor, a funding body, or a dissertation committee) that your research topic is relevant and worthy of being conducted.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, November 21). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

How to Write a Research Proposal: (with Examples & Templates)

- Table of Contents

Before conducting a study, a research proposal should be created that outlines researchers’ plans and methodology and is submitted to the concerned evaluating organization or person. Creating a research proposal is an important step to ensure that researchers are on track and are moving forward as intended. A research proposal can be defined as a detailed plan or blueprint for the proposed research that you intend to undertake. It provides readers with a snapshot of your project by describing what you will investigate, why it is needed, and how you will conduct the research.

Your research proposal should aim to explain to the readers why your research is relevant and original, that you understand the context and current scenario in the field, have the appropriate resources to conduct the research, and that the research is feasible given the usual constraints.

This article will describe in detail the purpose and typical structure of a research proposal , along with examples and templates to help you ace this step in your research journey.

What is a Research Proposal ?

A research proposal¹ ,² can be defined as a formal report that describes your proposed research, its objectives, methodology, implications, and other important details. Research proposals are the framework of your research and are used to obtain approvals or grants to conduct the study from various committees or organizations. Consequently, research proposals should convince readers of your study’s credibility, accuracy, achievability, practicality, and reproducibility.

With research proposals , researchers usually aim to persuade the readers, funding agencies, educational institutions, and supervisors to approve the proposal. To achieve this, the report should be well structured with the objectives written in clear, understandable language devoid of jargon. A well-organized research proposal conveys to the readers or evaluators that the writer has thought out the research plan meticulously and has the resources to ensure timely completion.

Purpose of Research Proposals

A research proposal is a sales pitch and therefore should be detailed enough to convince your readers, who could be supervisors, ethics committees, universities, etc., that what you’re proposing has merit and is feasible . Research proposals can help students discuss their dissertation with their faculty or fulfill course requirements and also help researchers obtain funding. A well-structured proposal instills confidence among readers about your ability to conduct and complete the study as proposed.

Research proposals can be written for several reasons:³

- To describe the importance of research in the specific topic

- Address any potential challenges you may encounter

- Showcase knowledge in the field and your ability to conduct a study

- Apply for a role at a research institute

- Convince a research supervisor or university that your research can satisfy the requirements of a degree program

- Highlight the importance of your research to organizations that may sponsor your project

- Identify implications of your project and how it can benefit the audience

What Goes in a Research Proposal?

Research proposals should aim to answer the three basic questions—what, why, and how.

The What question should be answered by describing the specific subject being researched. It should typically include the objectives, the cohort details, and the location or setting.

The Why question should be answered by describing the existing scenario of the subject, listing unanswered questions, identifying gaps in the existing research, and describing how your study can address these gaps, along with the implications and significance.

The How question should be answered by describing the proposed research methodology, data analysis tools expected to be used, and other details to describe your proposed methodology.

Research Proposal Example

Here is a research proposal sample template (with examples) from the University of Rochester Medical Center. 4 The sections in all research proposals are essentially the same although different terminology and other specific sections may be used depending on the subject.

Structure of a Research Proposal

If you want to know how to make a research proposal impactful, include the following components:¹

1. Introduction

This section provides a background of the study, including the research topic, what is already known about it and the gaps, and the significance of the proposed research.

2. Literature review

This section contains descriptions of all the previous relevant studies pertaining to the research topic. Every study cited should be described in a few sentences, starting with the general studies to the more specific ones. This section builds on the understanding gained by readers in the Introduction section and supports it by citing relevant prior literature, indicating to readers that you have thoroughly researched your subject.

3. Objectives

Once the background and gaps in the research topic have been established, authors must now state the aims of the research clearly. Hypotheses should be mentioned here. This section further helps readers understand what your study’s specific goals are.

4. Research design and methodology

Here, authors should clearly describe the methods they intend to use to achieve their proposed objectives. Important components of this section include the population and sample size, data collection and analysis methods and duration, statistical analysis software, measures to avoid bias (randomization, blinding), etc.

5. Ethical considerations

This refers to the protection of participants’ rights, such as the right to privacy, right to confidentiality, etc. Researchers need to obtain informed consent and institutional review approval by the required authorities and mention this clearly for transparency.

6. Budget/funding

Researchers should prepare their budget and include all expected expenditures. An additional allowance for contingencies such as delays should also be factored in.

7. Appendices

This section typically includes information that supports the research proposal and may include informed consent forms, questionnaires, participant information, measurement tools, etc.

8. Citations

Important Tips for Writing a Research Proposal

Writing a research proposal begins much before the actual task of writing. Planning the research proposal structure and content is an important stage, which if done efficiently, can help you seamlessly transition into the writing stage. 3,5

The Planning Stage

- Manage your time efficiently. Plan to have the draft version ready at least two weeks before your deadline and the final version at least two to three days before the deadline.

- What is the primary objective of your research?

- Will your research address any existing gap?

- What is the impact of your proposed research?

- Do people outside your field find your research applicable in other areas?

- If your research is unsuccessful, would there still be other useful research outcomes?

The Writing Stage

- Create an outline with main section headings that are typically used.

- Focus only on writing and getting your points across without worrying about the format of the research proposal , grammar, punctuation, etc. These can be fixed during the subsequent passes. Add details to each section heading you created in the beginning.

- Ensure your sentences are concise and use plain language. A research proposal usually contains about 2,000 to 4,000 words or four to seven pages.

- Don’t use too many technical terms and abbreviations assuming that the readers would know them. Define the abbreviations and technical terms.

- Ensure that the entire content is readable. Avoid using long paragraphs because they affect the continuity in reading. Break them into shorter paragraphs and introduce some white space for readability.

- Focus on only the major research issues and cite sources accordingly. Don’t include generic information or their sources in the literature review.

- Proofread your final document to ensure there are no grammatical errors so readers can enjoy a seamless, uninterrupted read.

- Use academic, scholarly language because it brings formality into a document.

- Ensure that your title is created using the keywords in the document and is neither too long and specific nor too short and general.

- Cite all sources appropriately to avoid plagiarism.

- Make sure that you follow guidelines, if provided. This includes rules as simple as using a specific font or a hyphen or en dash between numerical ranges.

- Ensure that you’ve answered all questions requested by the evaluating authority.

Key Takeaways

Here’s a summary of the main points about research proposals discussed in the previous sections:

- A research proposal is a document that outlines the details of a proposed study and is created by researchers to submit to evaluators who could be research institutions, universities, faculty, etc.

- Research proposals are usually about 2,000-4,000 words long, but this depends on the evaluating authority’s guidelines.

- A good research proposal ensures that you’ve done your background research and assessed the feasibility of the research.

- Research proposals have the following main sections—introduction, literature review, objectives, methodology, ethical considerations, and budget.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. How is a research proposal evaluated?

A1. In general, most evaluators, including universities, broadly use the following criteria to evaluate research proposals . 6

- Significance —Does the research address any important subject or issue, which may or may not be specific to the evaluator or university?

- Content and design —Is the proposed methodology appropriate to answer the research question? Are the objectives clear and well aligned with the proposed methodology?

- Sample size and selection —Is the target population or cohort size clearly mentioned? Is the sampling process used to select participants randomized, appropriate, and free of bias?

- Timing —Are the proposed data collection dates mentioned clearly? Is the project feasible given the specified resources and timeline?

- Data management and dissemination —Who will have access to the data? What is the plan for data analysis?

Q2. What is the difference between the Introduction and Literature Review sections in a research proposal ?

A2. The Introduction or Background section in a research proposal sets the context of the study by describing the current scenario of the subject and identifying the gaps and need for the research. A Literature Review, on the other hand, provides references to all prior relevant literature to help corroborate the gaps identified and the research need.

Q3. How long should a research proposal be?

A3. Research proposal lengths vary with the evaluating authority like universities or committees and also the subject. Here’s a table that lists the typical research proposal lengths for a few universities.

| Arts programs | 1,000-1,500 | |

| University of Birmingham | Law School programs | 2,500 |

| PhD | 2,500 | |

| 2,000 | ||

| Research degrees | 2,000-3,500 |

Q4. What are the common mistakes to avoid in a research proposal ?

A4. Here are a few common mistakes that you must avoid while writing a research proposal . 7

- No clear objectives: Objectives should be clear, specific, and measurable for the easy understanding among readers.

- Incomplete or unconvincing background research: Background research usually includes a review of the current scenario of the particular industry and also a review of the previous literature on the subject. This helps readers understand your reasons for undertaking this research because you identified gaps in the existing research.

- Overlooking project feasibility: The project scope and estimates should be realistic considering the resources and time available.

- Neglecting the impact and significance of the study: In a research proposal , readers and evaluators look for the implications or significance of your research and how it contributes to the existing research. This information should always be included.

- Unstructured format of a research proposal : A well-structured document gives confidence to evaluators that you have read the guidelines carefully and are well organized in your approach, consequently affirming that you will be able to undertake the research as mentioned in your proposal.

- Ineffective writing style: The language used should be formal and grammatically correct. If required, editors could be consulted, including AI-based tools such as Paperpal , to refine the research proposal structure and language.

Thus, a research proposal is an essential document that can help you promote your research and secure funds and grants for conducting your research. Consequently, it should be well written in clear language and include all essential details to convince the evaluators of your ability to conduct the research as proposed.

This article has described all the important components of a research proposal and has also provided tips to improve your writing style. We hope all these tips will help you write a well-structured research proposal to ensure receipt of grants or any other purpose.

References

- Sudheesh K, Duggappa DR, Nethra SS. How to write a research proposal? Indian J Anaesth. 2016;60(9):631-634. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5037942/

- Writing research proposals. Harvard College Office of Undergraduate Research and Fellowships. Harvard University. Accessed July 14, 2024. https://uraf.harvard.edu/apply-opportunities/app-components/essays/research-proposals

- What is a research proposal? Plus how to write one. Indeed website. Accessed July 17, 2024. https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/research-proposal

- Research proposal template. University of Rochester Medical Center. Accessed July 16, 2024. https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/MediaLibraries/URMCMedia/pediatrics/research/documents/Research-proposal-Template.pdf

- Tips for successful proposal writing. Johns Hopkins University. Accessed July 17, 2024. https://research.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Tips-for-Successful-Proposal-Writing.pdf

- Formal review of research proposals. Cornell University. Accessed July 18, 2024. https://irp.dpb.cornell.edu/surveys/survey-assessment-review-group/research-proposals

- 7 Mistakes you must avoid in your research proposal. Aveksana (via LinkedIn). Accessed July 17, 2024. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/7-mistakes-you-must-avoid-your-research-proposal-aveksana-cmtwf/

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

How to write a phd research proposal.

- What are the Benefits of Generative AI for Academic Writing?

- How to Avoid Plagiarism When Using Generative AI Tools

- What is Hedging in Academic Writing?

How to Write Your Research Paper in APA Format

The future of academia: how ai tools are changing the way we do research, you may also like, dissertation printing and binding | types & comparison , what is a dissertation preface definition and examples , how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), maintaining academic integrity with paperpal’s generative ai writing..., research funding basics: what should a grant proposal..., how to write an abstract in research papers..., how to write dissertation acknowledgements.

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

The goal of a research proposal is twofold: to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting research are governed by standards of the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, therefore, the guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to determine that the research problem has not been adequately addressed or has been answered ineffectively and, in so doing, become better at locating pertinent scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of conducting scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those findings. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your proposal is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to investigate.

- Why do you want to do the research? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of in-depth study. A successful research proposal must answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to conduct the research? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having difficulty formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here for strategies in developing a problem to study.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise . A research proposal must be focused and not be "all over the map" or diverge into unrelated tangents without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review . Proposals should be grounded in foundational research that lays a foundation for understanding the development and scope of the the topic and its relevance.

- Failure to delimit the contextual scope of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.]. As with any research paper, your proposed study must inform the reader how and in what ways the study will frame the problem.

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research . This is critical. In many workplace settings, the research proposal is a formal document intended to argue for why a study should be funded.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar . Although a research proposal does not represent a completed research study, there is still an expectation that it is well-written and follows the style and rules of good academic writing.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues . Your proposal should focus on only a few key research questions in order to support the argument that the research needs to be conducted. Minor issues, even if valid, can be mentioned but they should not dominate the overall narrative.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal. Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing most college-level academic papers, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. The text of proposals generally vary in length between ten and thirty-five pages, followed by the list of references. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like, "Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

Most proposals should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea based on a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and to be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in two to four paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that research problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Answer the "So What?" question by explaining why this is important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This is where you explain the scope and context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. It can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is most relevant in explaining the aims of your research.

To that end, while there are no prescribed rules for establishing the significance of your proposed study, you should attempt to address some or all of the following:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing; be sure to answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care?].

- Describe the major issues or problems examined by your research. This can be in the form of questions to be addressed. Be sure to note how your proposed study builds on previous assumptions about the research problem.

- Explain the methods you plan to use for conducting your research. Clearly identify the key sources you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Describe the boundaries of your proposed research in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you plan to study, but what aspects of the research problem will be excluded from the study.

- If necessary, provide definitions of key concepts, theories, or terms.

III. Literature Review

Connected to the background and significance of your study is a section of your proposal devoted to a more deliberate review and synthesis of prior studies related to the research problem under investigation . The purpose here is to place your project within the larger whole of what is currently being explored, while at the same time, demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methodological approaches they have used, and what is your understanding of their findings and, when stated, their recommendations. Also pay attention to any suggestions for further research.

Since a literature review is information dense, it is crucial that this section is intelligently structured to enable a reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your proposed study in relation to the arguments put forth by other researchers. A good strategy is to break the literature into "conceptual categories" [themes] rather than systematically or chronologically describing groups of materials one at a time. Note that conceptual categories generally reveal themselves after you have read most of the pertinent literature on your topic so adding new categories is an on-going process of discovery as you review more studies. How do you know you've covered the key conceptual categories underlying the research literature? Generally, you can have confidence that all of the significant conceptual categories have been identified if you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations that are being made.

NOTE: Do not shy away from challenging the conclusions made in prior research as a basis for supporting the need for your proposal. Assess what you believe is missing and state how previous research has failed to adequately examine the issue that your study addresses. Highlighting the problematic conclusions strengthens your proposal. For more information on writing literature reviews, GO HERE .

To help frame your proposal's review of prior research, consider the "five C’s" of writing a literature review:

- Cite , so as to keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methodologies, and findings expressed in the literature: what do the authors agree on? Who applies similar approaches to analyzing the research problem?

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methodologies, approaches, and controversies expressed in the literature: describe what are the major areas of disagreement, controversy, or debate among scholars?

- Critique the literature: Which arguments are more persuasive, and why? Which approaches, findings, and methodologies seem most reliable, valid, or appropriate, and why? Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what an author says/does [e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, etc.].

- Connect the literature to your own area of research and investigation: how does your own work draw upon, depart from, synthesize, or add a new perspective to what has been said in the literature?

IV. Research Design and Methods

This section must be well-written and logically organized because you are not actually doing the research, yet, your reader must have confidence that you have a plan worth pursuing . The reader will never have a study outcome from which to evaluate whether your methodological choices were the correct ones. Thus, the objective here is to convince the reader that your overall research design and proposed methods of analysis will correctly address the problem and that the methods will provide the means to effectively interpret the potential results. Your design and methods should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

Describe the overall research design by building upon and drawing examples from your review of the literature. Consider not only methods that other researchers have used, but methods of data gathering that have not been used but perhaps could be. Be specific about the methodological approaches you plan to undertake to obtain information, the techniques you would use to analyze the data, and the tests of external validity to which you commit yourself [i.e., the trustworthiness by which you can generalize from your study to other people, places, events, and/or periods of time].

When describing the methods you will use, be sure to cover the following:

- Specify the research process you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results obtained in relation to the research problem. Don't just describe what you intend to achieve from applying the methods you choose, but state how you will spend your time while applying these methods [e.g., coding text from interviews to find statements about the need to change school curriculum; running a regression to determine if there is a relationship between campaign advertising on social media sites and election outcomes in Europe ].

- Keep in mind that the methodology is not just a list of tasks; it is a deliberate argument as to why techniques for gathering information add up to the best way to investigate the research problem. This is an important point because the mere listing of tasks to be performed does not demonstrate that, collectively, they effectively address the research problem. Be sure you clearly explain this.

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers and pitfalls in carrying out your research design and explain how you plan to address them. No method applied to research in the social and behavioral sciences is perfect, so you need to describe where you believe challenges may exist in obtaining data or accessing information. It's always better to acknowledge this than to have it brought up by your professor!

V. Preliminary Suppositions and Implications

Just because you don't have to actually conduct the study and analyze the results, doesn't mean you can skip talking about the analytical process and potential implications . The purpose of this section is to argue how and in what ways you believe your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the subject area under investigation. Depending on the aims and objectives of your study, describe how the anticipated results will impact future scholarly research, theory, practice, forms of interventions, or policy making. Note that such discussions may have either substantive [a potential new policy], theoretical [a potential new understanding], or methodological [a potential new way of analyzing] significance. When thinking about the potential implications of your study, ask the following questions:

- What might the results mean in regards to challenging the theoretical framework and underlying assumptions that support the study?

- What suggestions for subsequent research could arise from the potential outcomes of the study?

- What will the results mean to practitioners in the natural settings of their workplace, organization, or community?

- Will the results influence programs, methods, and/or forms of intervention?

- How might the results contribute to the solution of social, economic, or other types of problems?

- Will the results influence policy decisions?

- In what way do individuals or groups benefit should your study be pursued?

- What will be improved or changed as a result of the proposed research?

- How will the results of the study be implemented and what innovations or transformative insights could emerge from the process of implementation?

NOTE: This section should not delve into idle speculation, opinion, or be formulated on the basis of unclear evidence . The purpose is to reflect upon gaps or understudied areas of the current literature and describe how your proposed research contributes to a new understanding of the research problem should the study be implemented as designed.

ANOTHER NOTE : This section is also where you describe any potential limitations to your proposed study. While it is impossible to highlight all potential limitations because the study has yet to be conducted, you still must tell the reader where and in what form impediments may arise and how you plan to address them.

VI. Conclusion

The conclusion reiterates the importance or significance of your proposal and provides a brief summary of the entire study . This section should be only one or two paragraphs long, emphasizing why the research problem is worth investigating, why your research study is unique, and how it should advance existing knowledge.

Someone reading this section should come away with an understanding of:

- Why the study should be done;

- The specific purpose of the study and the research questions it attempts to answer;

- The decision for why the research design and methods used where chosen over other options;

- The potential implications emerging from your proposed study of the research problem; and

- A sense of how your study fits within the broader scholarship about the research problem.

VII. Citations

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used . In a standard research proposal, this section can take two forms, so consult with your professor about which one is preferred.

- References -- a list of only the sources you actually used in creating your proposal.

- Bibliography -- a list of everything you used in creating your proposal, along with additional citations to any key sources relevant to understanding the research problem.

In either case, this section should testify to the fact that you did enough preparatory work to ensure the project will complement and not just duplicate the efforts of other researchers. It demonstrates to the reader that you have a thorough understanding of prior research on the topic.

Most proposal formats have you start a new page and use the heading "References" or "Bibliography" centered at the top of the page. Cited works should always use a standard format that follows the writing style advised by the discipline of your course [e.g., education=APA; history=Chicago] or that is preferred by your professor. This section normally does not count towards the total page length of your research proposal.

Develop a Research Proposal: Writing the Proposal. Office of Library Information Services. Baltimore County Public Schools; Heath, M. Teresa Pereira and Caroline Tynan. “Crafting a Research Proposal.” The Marketing Review 10 (Summer 2010): 147-168; Jones, Mark. “Writing a Research Proposal.” In MasterClass in Geography Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning . Graham Butt, editor. (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), pp. 113-127; Juni, Muhamad Hanafiah. “Writing a Research Proposal.” International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences 1 (September/October 2014): 229-240; Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005; Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Punch, Keith and Wayne McGowan. "Developing and Writing a Research Proposal." In From Postgraduate to Social Scientist: A Guide to Key Skills . Nigel Gilbert, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), 59-81; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences , Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- << Previous: Writing a Reflective Paper

- Next: Generative AI and Writing >>

- Last Updated: Jun 3, 2024 9:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

- Privacy Policy

Home » How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

How To Write a Research Proposal

Writing a Research proposal involves several steps to ensure a well-structured and comprehensive document. Here is an explanation of each step:

1. Title and Abstract

- Choose a concise and descriptive title that reflects the essence of your research.

- Write an abstract summarizing your research question, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes. It should provide a brief overview of your proposal.

2. Introduction:

- Provide an introduction to your research topic, highlighting its significance and relevance.

- Clearly state the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Discuss the background and context of the study, including previous research in the field.

3. Research Objectives

- Outline the specific objectives or aims of your research. These objectives should be clear, achievable, and aligned with the research problem.

4. Literature Review:

- Conduct a comprehensive review of relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings, identify gaps, and highlight how your research will contribute to the existing knowledge.

5. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to employ to address your research objectives.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques you will use.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate and suitable for your research.

6. Timeline:

- Create a timeline or schedule that outlines the major milestones and activities of your research project.

- Break down the research process into smaller tasks and estimate the time required for each task.

7. Resources:

- Identify the resources needed for your research, such as access to specific databases, equipment, or funding.

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources to carry out your research effectively.

8. Ethical Considerations:

- Discuss any ethical issues that may arise during your research and explain how you plan to address them.

- If your research involves human subjects, explain how you will ensure their informed consent and privacy.

9. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

- Clearly state the expected outcomes or results of your research.

- Highlight the potential impact and significance of your research in advancing knowledge or addressing practical issues.

10. References:

- Provide a list of all the references cited in your proposal, following a consistent citation style (e.g., APA, MLA).

11. Appendices:

- Include any additional supporting materials, such as survey questionnaires, interview guides, or data analysis plans.

Research Proposal Format

The format of a research proposal may vary depending on the specific requirements of the institution or funding agency. However, the following is a commonly used format for a research proposal:

1. Title Page:

- Include the title of your research proposal, your name, your affiliation or institution, and the date.

2. Abstract:

- Provide a brief summary of your research proposal, highlighting the research problem, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes.

3. Introduction:

- Introduce the research topic and provide background information.

- State the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Explain the significance and relevance of the research.

- Review relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings and identify gaps in the existing knowledge.

- Explain how your research will contribute to filling those gaps.

5. Research Objectives:

- Clearly state the specific objectives or aims of your research.